Amusing ourselves to death

Healthy minds, death of social media, Raghu Rajan, bond markets, personality traits and career outcomes and more.

Ok, here’s what I found on the dumpster fire that is the interweb this week:

Alain de Botton on a healthy mind.

The end of open social media.

Out the money reads: Did SEO ruin the internet, future of NGOs, climate change impact in poor countries, downside of EVs and more.

Raghuram Rajan on the 2008 crisis, central banking, inequality, unconventional monetary policy, and more.

Bond markets are going electronic in Europe.

In the money reads: emerging markets resilience, performance chasing, college wage premium, personality traits, career success, and more.

A few good thoughts

I came across writer Alain de Botton’s beautiful post on the wondrous human mind, thanks to The Marginalian. Here are a few evocative excerpts:

So efficient and hushed are our brains in their day to day operations, we are apt to miss what an extraordinary and complicated achievement it is to feel mentally well. A mind in a healthy state is, in the background, continually performing a near-miraculous set of manoeuvres that underpin our moods of clear-sightedness and purpose.

A healthy mind knows how to hope; it identifies and then hangs on tenaciously to a few reasons to keep going. Grounds for despair, anger and sadness are, of course, all around. But the healthy mind knows how to bracket negativity in the name of endurance. It clings to evidence of what is still beautiful and kind. It remembers to appreciate; it can – despite everything – still look forward to a hot bath, some dried fruit or dark chocolate, a chat with a friend, or a satisfying day of work. It refuses to let itself be silenced by all the many sensible arguments in favour of rage and despondency.

A Therapeutic Journey: Lessons from the School of Life | Extract | Hat tip to Maria Popova

Another beautiful quote I found on the site:

“The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven..”

―John Milton

Rummaging through quotes on Goodreads has become a new pastime for me. I’ve heard a version of this quote from other accomplished and smart people that I look up to as well:

“For me, I am driven by two main philosophies: know more today about the world than I knew yesterday and lessen the suffering of others. You'd be surprised how far that gets you.”

― Neil deGrasse Tyson

“Sometimes, carrying on, just carrying on, is the superhuman achievement.”

―Albert Camus

Jim O'Shaughnessy shared this:

Anthony de Mello's four truths:

1. Attachment or Happiness, you must pick one.

2. You didn't pick your original attachments, you can rewrite them.

3. To be truly alive, you must have Perspective.

4. No thing or person outside you has the power to make you happy. Only you can.

Out of the money

The end of open social media

It’s hard not to look at statistics like this and be shocked, even though we know them at some level. It’s nuts.

The first popular social network in my circle was Orkut by Google. I don’t have a good recollection of what I used to do on the platform; it couldn’t have been anything useful. Soon, Orkut withered as Facebook became popular. I have fairly good memories of the dumb things I used to do on it. The earliest memory I have of Facebook is using the poke feature. Remember that? It’s something you did to annoy your friends.

These were good times. Social platforms were still called social networks, not social media. You checked in with distant friends, shared memories, rediscovered old acquaintances, found your soulmates, and sometimes even did accidentally useful things. Fun times. Hundreds of social media platforms came and went, but Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram remained popular. They became part of our daily lives. Without realizing it, we were getting hooked on the tiny dopamine hits of likes, pokes, shares, and retweets. But it was still okay; we were just having innocent fun.

Somewhere along the way, social networks became social media, and it all went to shit. The trouble started when social platforms started pushing news and branded content compared to updates from friends. Instead of poking each other, we started arguing about politics and other divisive topics. The platforms wanted engagement, and what better way than to enrage people? This strategy started to backfire starting around 2015.

Platforms had started to go to shit long before, but the 2016 US election, in which Donald Trump won, was the moment when the developed world went, “Oh shit, we have a problem.” Trump brought out the worst in people, and political polarization exploded. Social platforms became outlets for people to express their politically motivated hatred and animosity. The incentives of the platform to peddle extreme stuff further inflamed the situation. It wasn’t just the US; partisanship and polarization rose in several countries across the world, and platforms were at the heart of the issue. Social networks not only became places where you bickered and argued over pointless shit with people you otherwise liked but also with random people from Albania and Montenegro.

The platforms—Facebook in particular—did a sharp U-turn around 2017–18 as they deprioritized news content, but it was too late. There was a time when the narrative about social platforms was that they would connect people and even make the world a better place. Remember the Facebook and Twitter revolutions in Middle Eastern countries like Tunisia, Iran, and Egypt? Of course, the role of platforms in popular uprisings was vastly overstated. This period marked the end of the fun era of social networks. The shift from “social networks” to “social media” was complete.

It’s just stunning that the narrative about social networks went from them being saviors of democracy to destroyers of civilization. Today, social media platforms are charged with abetting genocide, dividing people, tearing apart the social fabric, and unleashing a global mental health crisis among young people.

After their divorce with news, the priorities of the platforms changed. They no longer cared about pointless shit like connecting people and making the world a better place. Platforms are businesses, and business interests dictate the direction they take—it’s shareholder capitalism, baby. The shareholders and venture capital investors were clear on what they wanted—they wanted moar growth, more clicks, moar engagement, and moar money. Moar more!

Unlike most other businesses on Earth that live and die by their customers’ demands, social media services are caught trying to satisfy both their users and the people actually paying for it all: investors and advertisers.

The needs of these groups are dramatically different. Users want what the platform was originally for — be it ephemeral messaging, sharing photos, or otherwise. Surprising, energized spaces to connect with friends in a new way. But these use cases inevitably have a limit. You can only post so many photos. You only have so many friends to message. And for investors and advertisers, that’s a problem. So each social network has to find ways to make you send another photo, or it has to deploy a brand-new feature and encourage you to use that, too. More usage, more space for ads, more money for investors. — Ellis Hamburger

Platforms get all the blame, but it’s not like the users were innocent. It takes two to tango. The engagement-engagement loop disfigured the platforms. The platforms were influencing us, and our behavior was influencing them. I want to be clear that it's easy to paint platforms as technological manifestations of Darth Vader. Are they responsible for all the ills that plague society? The research is unclear on that, but they had arole,e and that much is clear.

When I spoke with Nyhan, he told me much the same thing: “The most credible research is way out of line with the takes.” He noted, of extremist content and misinformation, that reliable research that “measures exposure to these things finds that the people consuming this content are small minorities who have extreme views already.” The problem with the bulk of the earlier research, Nyhan told me, is that it’s almost all correlational. “Many of these studies will find polarization on social media,” he said. “But that might just be the society we live in reflected on social media!” He hastened to add, “Not that this is untroubling, and none of this is to let these companies, which are exercising a lot of power with very little scrutiny, off the hook. But a lot of the criticisms of them are very poorly founded. . . . The expansion of Internet access coincides with fifteen other trends over time, and separating them is very difficult. The lack of good data is a huge problem insofar as it lets people project their own fears into this area.” He told me, “It’s hard to weigh in on the side of ‘We don’t know, the evidence is weak,’ because those points are always going to be drowned out in our discourse. But these arguments are systematically underprovided in the public domain.”

How the hell did we think that bringing the entire world online and letting everyone talk to each other would end well?

A global broadcast network where anyone can say anything to anyone else as often as possible, and where such people have come to think they deserve such a capacity, or even that withholding it amounts to censorship or suppression—that’s just a terrible idea from the outset. And it’s a terrible idea that is entirely and completely bound up with the concept of social media itself: systems erected and used exclusively to deliver an endless stream of content.

But now, perhaps, it can also end. The possible downfall of Facebook and Twitter (and others) is an opportunity—not to shift to some equivalent platform, but to embrace their ruination, something previously unthinkable. Ian Bogost, The Atlantic

Fast forward to 2023. Social media platforms feel like landfills. Gone are the days when embarrassing pictures of your friends and family used to fill our feeds. Now they are full of branded bullshit, exaggerated nonsense, engagement bait, hustle porn, and endless regurgitation of content that people steal from each other or, worse yet, copy from Wikipedia. Every day, tons and tons of fresh garbage are delivered to landfills. We don’t even care about the stench anymore because we’re used to it.

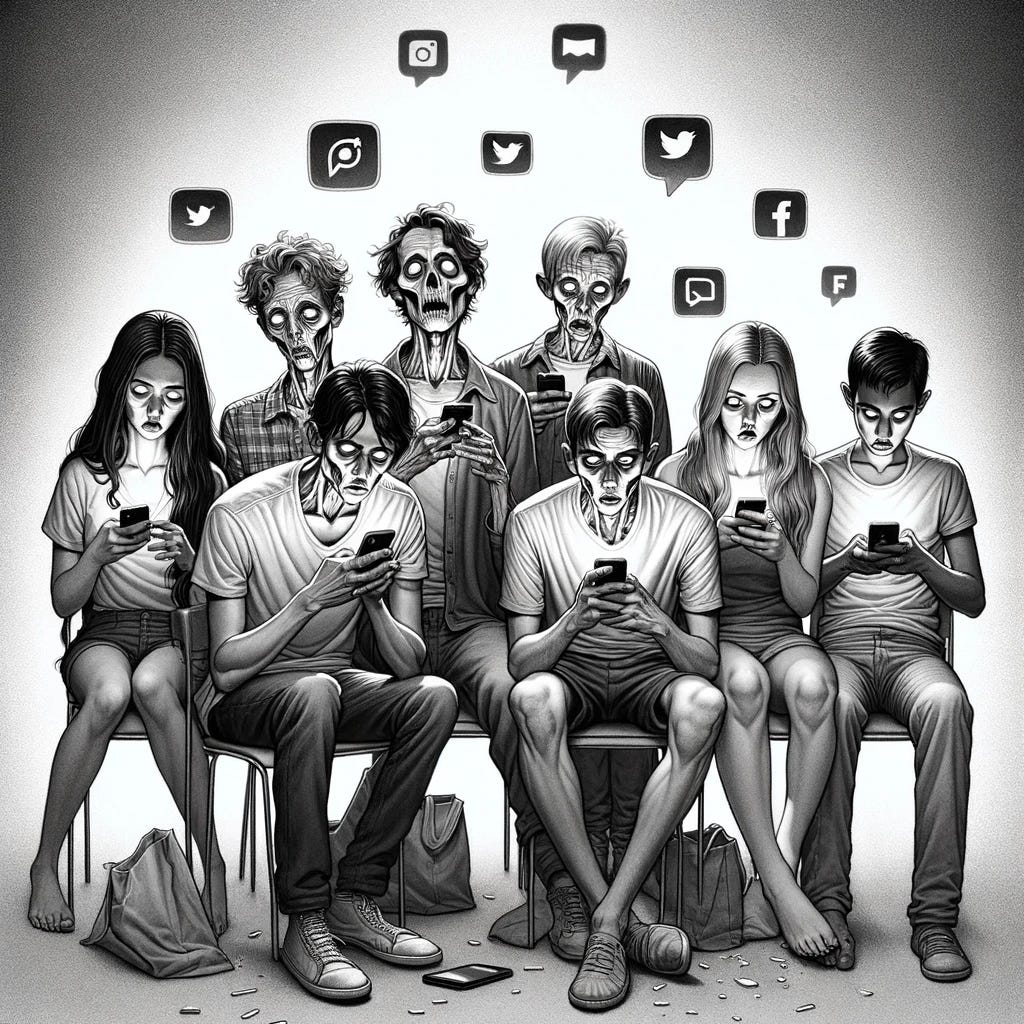

Then there are those short videos. People have become zombies as they watch one short video after another. Talking to another human being, staring at the birds in the distance, or, god forbid, stepping outside into the real world has become unimaginable. Swiping to find the next 60-second video is preferable compared to the agony of living. An entire generation of brain-dead people just hunched over and swiping up, desperate to escape life.

Add it all up, and the social web is changing in three crucial ways: It’s going from public to private; it’s shifting from growth and engagement, which broadly involves building good products that people like, to increasing revenue no matter the tradeoff; and it’s turning into an entertainment business. It turns out there’s no money in connecting people to each other, but there’s a fortune in putting ads between vertically scrolling videos that lots of people watch. So the “social media” era is giving way to the “media with a comments section” era, and everything is an entertainment platform now. Or, I guess, trying to do payments. Sometimes both. It gets weird. — David Pierce, editor-at-large of The Verge

In 2023, one thing that seems clear is that the era of open social media is over. Social networks just stopped being fun. We’re no longer social media “users”, we’re performers. Platforms have become performative hellscapes where people have to debase themselves to make a buck. People are twerking for Zuckbucks, Elonbucks, and YouTube bucks. In response to the fickle whims of the social algorithmic overlords, people, sorry "creators,” are having to demean themselves even more by escalating their ridiculousness.

Elon Musk woke up and asked him the question: What’s the best way to blow $44 billion? His answer was to buy an ossified social media platform and make it even worse than it was before. Zuck wanted to liberate humans from the tyranny of Silk Board and move us to the metaverse, but he’s taking a liking to the real world again. LinkedIn has become a parody of real life. A weird platform where even the most banal things are exaggerated. Things like “I farted in the elevator, and it changed my outlook about how to be professional, here are 5 things I learned.”

TikTok has become a cultural juggernaut in the US but faces an uncertain future after being banned in a large part of the world. For now, it’s the home of awkward and anxious teens craving the attention and validation of strangers in hopes that it will cure their acne outbreak. Instagram is no longer a cozy platform for amateur narcissists and terrible photographers. It’s filled with people peddling all sorts of nonsense, from magical jade stones that cure baldness if you put them in your butt to get-rich schemes. It’s a grifter’s paradise.

What comes next?

I’ve no idea, but here are some trends to watch out for.

Twitter seems to be circling the drain as high-profile users leave the platform and other users reduce their activity. Elon’s new rightward turn and the boosting of right-wing nutcasesares turning the platform into a wasteland.

Facebook is becoming less popular by the day.

The future of social media may be a lot less social. There’s growing evidence to show that people are moving to private places like WhatsApp, Discord, Telegram, Instagram DMs, etc.

Decentralized social networks like Mastadon and Bluesky are growing but are still light years away from the scale of centralized platforms.

I found this excerpt from Neil Postman's Amusing Ourselves to Death interesting. I fear he may be right:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny "failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distractions." In 1984, Orwell added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we fear will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we desire will ruin us.

This book is about the possibility that Huxley, not Orwell, was right.”

“When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when cultural life is redefined as a perpetual round of entertainments, when serious public conversation becomes a form of baby-talk, when, in short, a people become an audience, and their public business a vaudeville act, then a nation finds itself at risk; culture-death is a clear possibility.”

― Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

In my own experience, apart from the occasional shitposting, my social media posting activity had gone down. I doomscroll on Twitter because that's where all the smart people are. It's the only way I know of discovering the best articles, research, etc.

In the past couple of months, I’ve been increasingly using the Substack app. The explore feed is remarkably good, and the Substack algorithm is doing a good job of surfacing well-written perspectives. I haven’t found Substack Notes, a Twitter replacement, all that useful yet. The idea of this website was also, in a way, a reaction to the shittiness of social media platforms. I wanted to build a simple site where I could collect and organize some of the best things on the internet instead of dancing like a monkey to the whims of the platforms. Having said that, I may have to dance a little because I share the links to the posts on this website on the same platforms.

Dive deeper

The Internet Could Be So Good. Really

Why the Internet Isn't Fun Anymore

We’re Nearing Opinion Overload

Fidelity has marked down the value of Twitter/X by 65%

It's not just you. LinkedIn has gotten really weird.

I have more thoughts on the topic, but that’s for the coming weeks.

Good reads

The people who ruined the internet

“All the assholes that are out there paying shitty link-building companies to build shitty articles,” he said, “now they can go and use the free version of GPT.” Soon, he said, Google results would be even worse, dominated entirely by AI-generated crap designed to please the algorithms, produced and published at volumes far beyond anything humans could create, far beyond anything we’d ever seen before.

“They’re not gonna be able to stop the onslaught of it,” he said. Then he laughed and laughed, thinking about how puny and irrelevant Google seemed in comparison to the next generation of automated SEO. “You can’t stop it!”

The Oxfam scandal wasn’t the first of its kind. As far back as 2002, a report conducted by the UN Refugee Agency and Save the Children UK in west Africa found that agency workers from local and international NGOs, as well as UN agencies, were among the “prime sexual exploiters of refugee children”. Aid workers were accused of “using the very humanitarian assistance and services intended to benefit refugees as a tool of exploitation.”

The report, which included allegations against employees of some of the world’s biggest aid agencies, led only to patchy efforts to address the problem.

Years into a climate disaster, these people are eating the unthinkable

A gut wrenching story of how climate change is devastating the poorest regions on the planet.

Her entire days are “devoted to the lilies,” she said, and collecting them has proved so punishing — two-hour walks, hours more in the water, lugging them back home — that she’s developed chronic coughs, regular fevers, and found herself many mornings asking if she could bear to return to the water. “As long as my children are alive,” she’s told herself, “I’ll keep going.”

Why Norway — the poster child for electric cars — is having second thoughts

Electric vehicles are not an unalloyed good. A cautionary tale of Norway, where over 80% of cars sold are electric.

So I flew across the Atlantic to see what the fuss was about. I discovered a Norwegian EV bonanza that has indeed reduced emissions — but at the expense of compromising vital societal goals. Eye-popping EV subsidies have flowed largely to the affluent, contributing to the gap between rich and poor in a country proud of its egalitarian social policies.

Worse, the EV boom has hobbled Norwegian cities’ efforts to untether themselves from the automobile and enable residents to instead travel by transit or bicycle, decisions that do more to reduce emissions, enhance road safety, and enliven urban life than swapping a gas-powered car for an electric one.

Pair this this article on the myths of electric vehicles

Your guide to the guides for fixing the internet

I loved reading this post, especially the passage in bold. That’s a wonderful framing of how technologies evolve.

But I’m also personally a big believer in the idea that once you have a name for something happening online it’s already over. Whether it’s a meme or a trend or, in this case, a general vibe, the minute there’s a consensus as to what it is, it’s already its over to some degree. Which means I sort of think whatever that new status quo is, it’s already arrived and that the rut we feel like we’re in is possibly already over. Somewhere, at least. And while I share the affliction that all tech writers have, in that I crave applying some kind of order to the chaos of how technology evolves, the truth is that it just does a lot of the time. And there is some pocket of the web out there that has already defined our digital future. We just haven’t noticed it yet. (Though, it’s probably whatever furries are doing right now.)

I loved this post. Reading without purpose is a habit I’ve been deliberately trying to cultivate. This blog is based on the same premise—read without a purpose and share the good things.

At one point, Grant asked Nolan how he finds something that he’s passionate about. Nolan responded, in part:

“For me, it's all about trying new things. If you're going to write, you want to read a lot before you write, without any purpose. I love watching TV, love watching movies, preferably with no sense of purpose. Just being open to things that might inspire you—and staying open.”

Nolan reads “without any purpose.” I would argue, though, that there is a purpose in that: to find something that stimulates you but that you couldn’t have known to look for. I often wander bookstores, which I think of as places to find interests that I didn’t know I had.

In the money

Raghuram Rajan

Former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan is not a popular figure in certain Indian political circles. Whether you agree or disagree with him, he’s still one of the sharpest thinkers on issues of monetary policy and financial stability. He recently appeared on The Joe Walker Podcast, a favorite of mine, and I enjoyed listening to the conversation.

A few highlights from the conversation:

On his famous 2005 speech

In 2005, he gave a speech at the Jackson Hole symposium warning of hidden risks to the global financial system arising from distorted incentives. The event was supposed to be a celebration of the legacy of Alan Greenspan.

I remember leaving home and telling my wife, “This speech will either make or break me,” because I had an inkling that I was saying something important.

But I also knew that I was going out on a limb because I would look really stupid if I’d said, “Look, there are these risks building” and nothing actually happened. And, interestingly, at the end of the speech I went up to say hello to Chairman Greenspan and he was obviously not pleased. What was interesting was there were two private-sector people also there who were telling him, “Look, you’ve got to stop us from taking these risks.” And what was interesting was, that was the missing piece that somehow we had all convinced ourselves that the smartest guys in the room would have figured out how to manage the risks.

On his “let them eat credit” view

Well, there was a sense – which, again, like all ideas, there’s an element of good intent and truth to it – the sense that if we make credit easier, if we allow people to buy houses, for example, and they can ride the house appreciation, that’s good for their wealth, that’s good for their portfolios, but it also can take some of their worries away, including worries that they don’t have good jobs, they don’t have adequate human capital, et cetera.

Too much credit pushed too easily can actually do harm and even the people who get the credit can be harmed because they can get it at the wrong time. As prices are really going up they may not be able to afford the houses, they may not be able to afford the consumption that it made possible, they drew down on their home equity lines, and then found that house prices collapsed and there’s no equity anymore, in fact they were deeply in debt.

On the perils of pushing easy access to credit as means to financial inclusion

And so, there is more of a sense now that public policy plus the private sector may make it too easy to access for the disadvantaged to access credit, and they themselves may not have the capacity to understand what is reasonable. In fact, they’ll take whatever comes because their discounting of the future is much higher – “Sick child today. Let me try and get the child to a hospital. What if I have to borrow.” But then the loan has to be paid tomorrow. That’s when the lenders start hounding this person. I myself, while I was in India, was much more focused on pushing payments and other services as the lead into inclusion, rather than pushing credit as the first thing. Because it struck me that the problem with pushing credit was that before people know how to manage their finances, if they get easy credit, there’s a likelihood they will overborrow and then face problems down the line.

On central bank independence

I do think that central banking is a very political job. It may seem technocratic and, yeah, you think about what R-star is and you set interest rates with that in mind.

Where you think R-star is completely political. I shouldn’t say completely political; it cannot be devoid of politics. But your language, your persuasion, the extent of hostility that you face – all that is political

I don’t think they are. Technically, as a central bank chief, some countries will make it very hard to fire you. Does that mean that you can do what you want? No.

I don’t think it’s wise to completely put the central bank outside of any kind of control. I think unelected officials should have some oversight by the elected representatives of the people. I think there’s an optimal point where you respect them and you try not go too far away from what is politically acceptable. But there are times when there is something you need to do which will cause pain, which somebody who wanted to be elected in the next election would perhaps not espouse, but which you think is needed not just for the next election cycle, but for many election cycles down the line.

That’s when, if you have enough independence as a central bank, you can make the tough choice. But to completely ignore the elected representatives of the people all the time? Well, sometimes they actually have sensible ideas which you should be paying more attention to.

On incentives

The Goldman Sachses of the world – why would they go out on a limb? Why would they risk their firm’s capital? The missing piece, which to some extent I alluded to in the paper, was distorted incentives in the financial system – and that led to the tail risk-taking. The smartest guys were not immune to bad incentives.

On why just lowering interest rates after the 2008 crisis didn’t work

In other words, you had to do structural reforms. And this sounds like the annoying sort of old geezer who says whenever things are slowing down, “All you young pups, you always want to stimulate. You actually need to fix the underlying problems. Structural reforms.” But I do think, as a number of people have suggested, one of the problems with the low demand in industrial countries stems from inequality that the lower end could consume more, would consume more, but doesn’t have the incomes. But how do you generate more incomes at the lower end? You have to make them more capable of getting good jobs, which means focus on capabilities, skill building et cetera. And for all the talk about the China effect on the US, I think the reality is the US has a lousy system of training people in response to trade shocks. The trade adjustment mechanisms simply don’t work.

Tangential rabbit holes

Incentives and self-delusions

As I was writing this post, I came across psychologist Adam Mastroianni’s brilliant post on Goodharting ourselves, a reference to Goodhart’s law and how it applies to individuals as well.

"When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure"

Dr. Rajan’s observation on incentives reminded me of this passage from Mastroianni’s post:

It's not just me, of course. I've seen people melt down over lots of dumb games: Monopoly, Scrabble, Mario Kart, mini golf, charades, bowling, trivia, and croquet. Losing your cool after losing a game is mildly mortifying, but if 15 minutes of struggling for made-up points is enough to turn you into a howling, friendship-shredding monster, imagine how low you can sink when there's actual money and prestige on the line. If you take a high-paying job to "provide for your family" and then you never see that family and they end up hating you, if you claw your way to the top only to find that you still feel as empty up there as you did at the bottom, if you get so obsessed with success that you lie and cheat to get it, then guess what: you got Goodharted.

Dive deeper into the history of the 2008 global financial crisis.

I’ve been fascinated by the 2008 financial crisis for a long time, and I had written about it a little in an old post as well. One of the definitive books on the crisis is Crashed by historian Adam Tooze. I highly recommend the book, but if you want a quick summary, you can watch this video as well. Adam Tooze is an information monster. He has the remarkable ability to consume a torrent of information and spit out accessible summaries and explanations of complex phenomena. I highly recommend reading anything he writes, including his Substack. He’s a regular on panels and podcasts, talking about a wide range of important economic developments. In the upcoming editions, I will try to summarize some of his talks.

He also hosts a weekly podcast that I recommend listening to.

European bond markets are going electronic

I have some experience trading bonds in India. It’s a market that’s stuck in time, where everything happens over calls and WhatsApp messages. Despite all the regulatory moves to increase liquidity in bonds on the exchanges, things haven’t changed much. All the bond trading has now been pushed to request for quote' (RFQ) platforms on the exchanges, but the price negotiations still happen on calls. The trades are executed on RFQ instead of off-market transfers.

Bonds will never trade like equities in exchanges; it’s not the nature of the instrument, and it’s a global thing. Most retail investors are also better off not buying single-name papers and should stick to bond mutual funds. Which means on-market liquidity will always be limited.

But it looks like things are changing in Europe:

But while algorithms work well on the small trades that account for 60 per cent of European bond market activity, they’re not yet trusted with big and complicated stuff. Only liquid, recently issued bonds with a large outstanding basis and a high credit rating are considered sufficiently low-touch to be fed into the system. So while the median European trade is now electronic the category still only accounts for 30 per cent of total volume, Barclays finds.

Ken Rogoff on why emerging markets haven't been resilient despite soaring US interest rates. He attributes this to central bank independence, but if you scroll up and read what Raghu Rajan says, he says the notion of central bank independence is a bit of a myth.

But the single biggest factor behind emerging markets’ resilience has been the increased focus on central-bank independence. Once an obscure academic notion, the concept has evolved into a global norm over the past two decades. This approach, which is often referred to as “inflation targeting,” has enabled emerging-market central banks to assert their autonomy, even though they frequently place greater weight on exchange rates than any inflation-targeting model would suggest.

Performance-chasing is an universal truth

The red line in the chart indicates that fund managers have about five years before their investors turn their backs on them. After five years of underperformance, there is no stopping disappointed investors from leaving the fund. My personal experience with investors is that five years is a long time. Most investors will get nervous after six to twelve months of underperformance and leave you after two to three years of underperformance.

Yet, this research points to a simple investment strategy for fund selectors. Look at funds that underperformed in years six to ten before today. These are the funds that tend to follow styles that are likely to come back into favour in the next five years. And that may have a better chance of outperforming going forward than the funds that did well in the last five years or so.

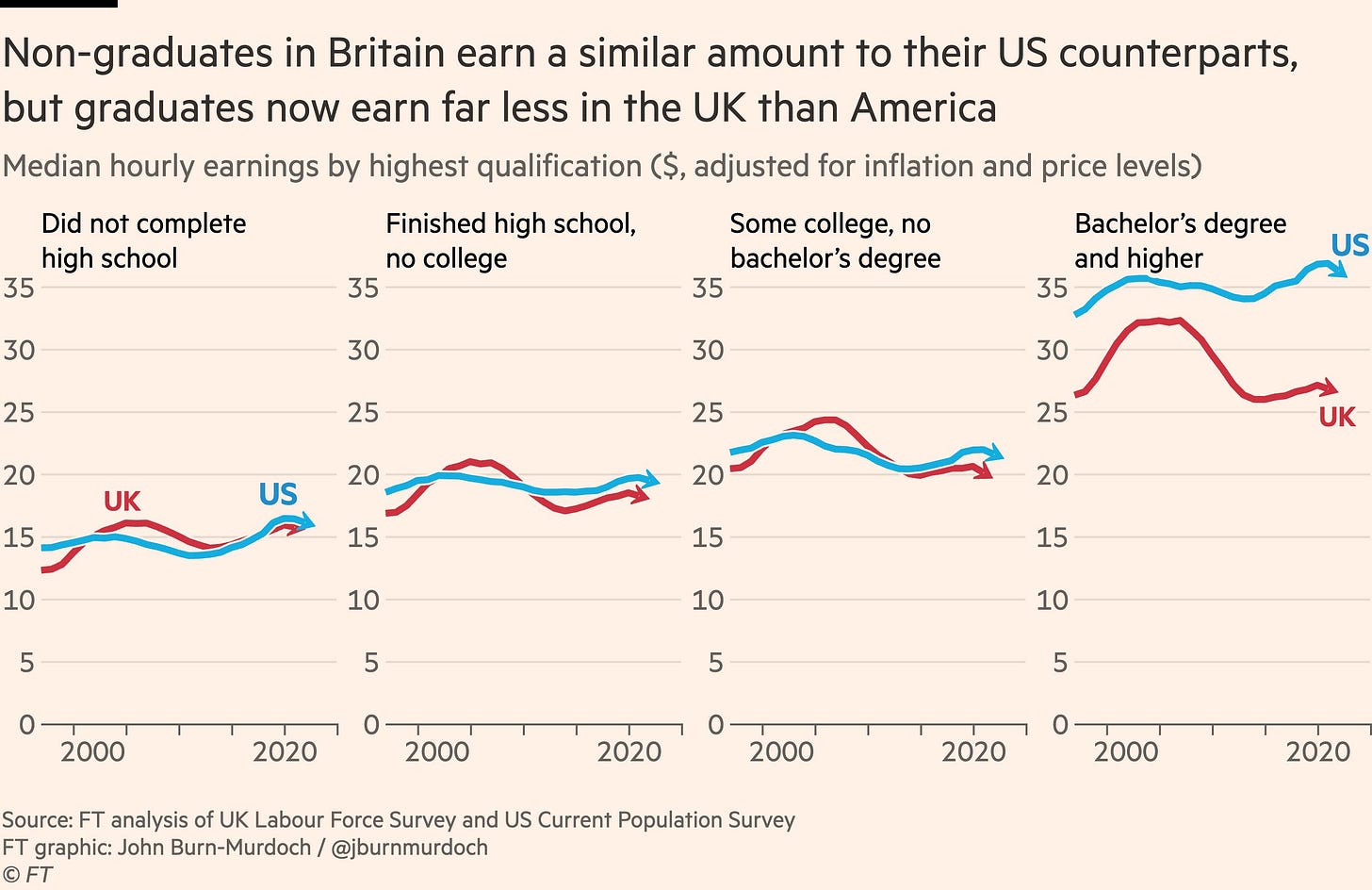

Fascinating discussion on the college wage premium in the United Kingdom and United States

What this chart is showing is that as each wave of graduates has entered the UK’s jobs market, on average they’re finding lower-grade jobs than the last, whereas in the US, each new wave of grads is met by a new wave of well-paid graduate jobs.

Other countries have the same rise in graduate numbers without the same decline in graduate earnings, because they’ve created good jobs. When people say Britain sends too many people to uni, they’re saying we’re not a country where skilled people can expect to find skilled jobs.

Short-changed graduates are just another symptom of the British economic disease. If you have low investment and low or zero productivity growth, then when your grads enter the job market, they’ll have fewer and weaker opportunities than grads in a country that had higher growth

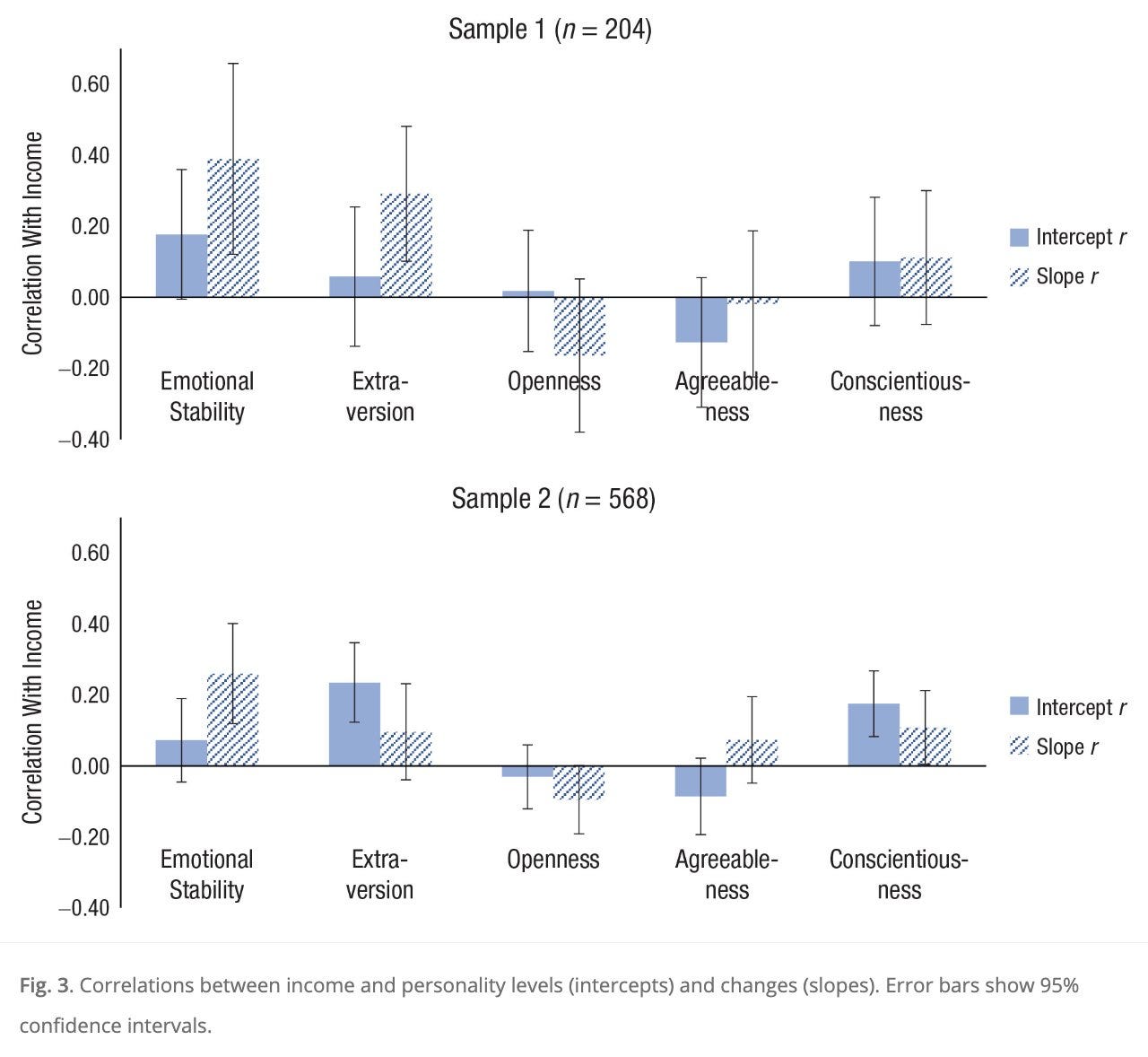

On a related note, research on what personality traits predict good career outcomes

In this research, we examined whether personality changes from adolescence to young adulthood predicted five early career outcomes: degree attainment, income, occupational prestige, career satisfaction, and job satisfaction. The study used two representative samples of Icelandic youth (Sample 1: n = 485, Sample 2: n = 1,290) and measured personality traits over 12 years (ages ~17 to 29 years). Results revealed that certain patterns of personality growth predicted career outcomes over and above adolescent trait levels and crystallized ability. Across both samples, the strongest effects were found for growth in emotional stability (income and career satisfaction), conscientiousness (career satisfaction), and extraversion (career satisfaction and job satisfaction). Initial trait levels also predicted career success, highlighting the long-term predictive power of personality. Overall, our findings show that personality has important effects on early career outcomes—both through stable trait levels and how people change over time. We discuss implications for public policy, for theoretical principles of personality development, and for young people making career decisions.

That’s it for this week. Lift your head up from those screens, go smell the fresh polluted air of Bangalore, meditate about life at Silk Board, and enjoy a long silent stroll on the main roads of Bangalore (becos we no footpath have).

![100+ Social Media Statistics You Need To Know In 2023 [All Networks] 100+ Social Media Statistics You Need To Know In 2023 [All Networks]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!2ciq!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1db6bfc1-a8d0-4a71-8463-9eef308d20c1_1203x1513.webp)