Fuck, shit, and everything in between: a quick history of swearing

For the love of cursing

Introduction

Fair warning: There's gratuitous profanity in this post. I mean, it's going to get really dirty, vulgar, obscene, and downright filthy. Some of you might be offended by what follows.

I don't care. I really don't.

But you can't blame me for not warning you.

With that, shall we fucking get on with it?

The Grrr and Uggg story

Let me tell you a story.

About 90,000 years ago, there was an awesome dude named Grrr. Life, as you can imagine, was hard back then. He was part of a group responsible for ensuring nobody in his village went hungry. Along with other dudes, he had to hunt and forage all day long. There was no Zomato yet, so as you can imagine, this was grueling work. If he didn't bust his ass, all his friends and family would die and become worm food.

Since Grrr worked hard all day, he would sleep in late and wake up around 7-8 AM, right at sunrise. One morning, he woke up around 8 AM and stepped outside to eject bodily effluvia. But before he started to ejaculate future plant nutrition from his body, he paused for a moment to take in the day.

It was a beautiful day. The sun was shining brightly, and a gentle breeze caressed his skin like the wrist of a tender lover. There was lush greenery all around, and his house sat in front of a small stream that flowed downhill. It was picturesque.

So he placed his hands on his hips, smiled, tilted his head back, and enjoyed the warmth of the early morning sun on his face. Suddenly, he felt a sharp, searing pain in his balls. He hunched over, hugging his stomach, and screamed out, "Fucking cock-piss mother-sucking shit-fucking ass cunt fucker!" He had been kicked right in the middle of his family jewels.

He looked back to see what happened, and there stood his dear friend Uggg, looking utterly perplexed. Uggg said, "What the fuck did you just say, you asshole?"

Unbeknownst to both Grrr and Uggg, they had just invented swearing.

True story.

Well, it's not literally true, but it's true enough in the sense that words are just arbitrary sounds that we assign meaning to. What we consider profane words probably originated in similar situations.

Why am I talking about swearing?

I have a doomscrolling problem. Unlike most people, I don't doomscroll on Instagram, but on Twitter, YouTube, and Pocket Casts. I'm not looking for entertainment; my disease is bookmarking interesting articles, videos, and podcasts to consume later. The gap between what I bookmark and what I actually manage to read or watch? That's the size of my regret.

During one such doomscrolling session on Pocket Casts, I happened to check out the feed of The Gray Area. On the podcast, the host Sean Illing discusses a wide variety of topics across politics, culture, tech, etc. with some of the most brilliant minds in those respective domains. I highly recommend the podcast.

Anyway, I can't recollect why I ended up on the podcast's feed, but I saw this episode titled "Swear like a philosopher," and I instantly bookmarked it for later listening.

For once, I actually went back and listened—and I went down what's easily one of the most delightful and fun rabbit holes of my life. During these doomscrolling sessions, I also ventured into exploring the need for wonder and awe [1, 2, 3].

As I learned more about swearing, it struck me that we often take the obvious for granted. We assume the things we're most familiar with are boring. But that's wrong, and it’s not just wrong—it’s fucking wrong. Swearing is one such thing. The more I explored, the more genuine wonder and awe I felt and the more hearty laughs I had.

What follows is an outline of what I learned about the delightful, fascinating, and perplexing history and psychology of swear words—and the act of swearing. I had a ton of fun digging into this topic, and I hope you do too. I'm by no means finished with it, and you'll see more posts on these themes in the future.

Whenever the topic of swearing comes up, the first thing that always comes to mind is George Carlin's legendary bit "The Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television."

George Carlin: That's what I was trying to figure out—those words that are always dirty. Not just sometimes, but fully, completely filthy.

In looking for these words, I kept finding new categories. We have so many ways of describing these "dirty" words—it's fascinating. In fact, we seem to have more ways to describe dirty words than we actually have dirty words. Doesn't that seem a little strange? It suggests that someone, somewhere, has been very interested in these words. They couldn't stop referring to them.

They've called them bad words, dirty, filthy, foul, vile, vulgar, coarse, in poor taste, unseemly. Street talk, gutter talk, locker room language, barrack talk. Bawdy, naughty, saucy, raunchy, rude, crude, lewd, lascivious, indecent, profane, obscene. Blue, off-color, risqué, suggestive. Cursing, cussing, swearing.

And after all that, all I could think of was: shit, piss, fuck, cunt, cocksucker, motherfucker, and tits.

The bit is just fucking brilliant! It’s pure fucking genius!

The other thing is John Goodman in Treme:

"Fuck you, you fucking fucks."

And then there's the sheer variety of the use of "cocksucker" in the phenomenally underrated show Deadwood.

There are anywhere between 170,000 and 1 million words in the English language. Of this vast body of words, there are a set of about 50 words that we have deemed offensive.

Isn't the sheer arbitrariness stunning?

I don't even think it's as many as 50 words. Sure, there are plenty of swear words, but the most taboo, heavy-hitting ones are fewer than 20. To be clear, I'm referring to swear words, not slurs. I'll delve into the distinction between the two later.

These words are deemed so dangerous and offensive that kings, queens, and governments throughout history have enacted laws against their usage. In the 16th and 17th centuries, people could be fined or even flogged for swearing.

This begs the question: What makes swear words special? This question reminds me of a quote by the great and poetic Carl Sagan:

If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.

As soon as I asked myself the question, "How did language originate and evolve?" I found myself tumbling down yet another rabbit hole—right alongside the one about swearing. So I started watching a bunch of videos from linguists and ordered more books to add to my I’ll never read all these goddamn books pile.

The origins of language

The topic of language origins is simultaneously fascinating, intimidating, and maddening. There are numerous theories, but there's little consensus among experts. From my cursory exploration of the topic, there seem to be two broad arguments. Before I get to them, I can't help but share this wonderful definition of what language is:

"Language is my whore, my mistress, my wife, my pen-friend, my check-out girl. Language is a complimentary moist lemon-scented cleansing square or handy freshen-up wipette. Language is the breath of God, the dew on a fresh apple, it's the soft rain of dust that falls into a shaft of morning sun when you pull from an old bookshelf a forgotten volume of erotic diaries; language is the faint scent of urine on a pair of boxer shorts, it's a half-remembered childhood birthday party, a creak on the stair, a spluttering match held to a frosted pane, the warm wet, trusting touch of a leaking nappy, the hulk of a charred Panzer, the underside of a granite boulder, the first downy growth on the upper lip of a Mediterranean girl, cobwebs long since overrun by an old Wellington boot." ― Stephen Fry

What an exquisite and marvelous definition!

There are two broad arguments about the origin of language:

Language is the product of biology, natural selection and evolution

Language is the product of culture

At the risk of butchering nuance, here are a few perspectives on the origin of languages that I discovered:

Noam Chomsky's View

The famed linguist argues that humans are born with an innate capacity for language, often referred to as "universal grammar"—a common structure underlying all languages.

Chomsky suggests that humans can speak because of a biological and genetic basis, and this ability appeared rather suddenly due to a genetic mutation roughly 90,000 years ago. Before Chomsky, the dominant behaviorist view held that language was purely learned through imitation and reinforcement.

Daniel Everett's Perspective

Everett rejects Chomsky's theory of universal grammar. He believes that language is a bio-cultural evolution that originated not with Homo sapiens but with Homo erectus about 1.5 million years ago.

According to him, symbolic thought was critical to the evolution of language, as evidenced by Homo erectus's ability to make tools. Everett argues that language evolved gradually in stages from sounds, signs, and gestures to the complex language we have today. This evolution was due to a Darwinian process in response to social and cultural pressures.

Steven Pinker's View

Famed psycholinguist Steven Pinker, like Chomsky, believes there's a biological basis for language—he calls it the "language instinct" in his wonderful book The Language Instinct. However, he disagrees with Chomsky's notion of a rigid universal grammar, calling it vague, and he's skeptical about Chomsky's views on evolution's role.

Pinker also argues against the idea that language is purely a cultural invention. He says it emerged gradually through natural selection to help humans communicate and cooperate.

Michael Tomasello

Michael Tomasello is an American developmental psychologist, and he's another notable figure who rejects Chomskian theories. Instead, he argues that human language emerged from our need to collaborate and cooperate.

He rejects a biological basis for language and instead posits that language evolved from simple gestures and then developed through observation, interaction, and imitation. Tomasello adds that while animals can gesture as well, what makes humans unique is our ability to share intentions: we understand what another person is thinking, infer what they want, and act accordingly.

Other Notable Theories

Michael Corballis: Language evolved from simple gestures and later developed into spoken language due to evolutionary pressures.

Mark Pagel: Language is a uniquely human trait that emerged due to genetic and cognitive mutations and was shaped by culture as much as evolution.

Daniel Levitin: Humans developed music before spoken language, using it to encode and transmit knowledge long before the spoken word.

Here’s an excerpt from Levitin’s conversation with Neil deGrasse Tyson:

Daniel Levitin: Think about the transmission of information within a culture and across generations. We do that by talking, but we also write things down. We've only had written language on this planet for about 5,000 years.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: In fact, it almost defines history.

Daniel Levitin: Well, that's right. Absolutely. But, you know, humans have been on the planet for 40,000 to 100,000 or 200,000 years longer than that, depending on how you define 'human.' So, for most of the time, we didn't have writing. What we believe, from studying contemporary hunter-gatherer societies that are cut off from Western civilization and industrialization, is that they lived the way humans might have 20,000 years ago.

We believe they used music to encode knowledge. For example, they would have a song that encodes, 'This is the route to the well,' or 'This is the route you take to the other well if this one goes dry.' Or a song that says, 'Don't go over that mountain because great-grandfather OG went there and the neighboring tribe killed him.' Or, 'This is how you make a watertight canoe,' or 'This is how you boil a plant so it's not poisonous.'

Why music? Because, first of all, the available evidence from my lab, and now many others around the world... The available evidence is that the neural structures that encode music are phylogenetically older than those that encode speech.

Chuck: Wow. So, evolutionarily, we were musicians before we were talking to one another?

Daniel Levitin: Yes, from a brain development standpoint, that's what it seems.

These are just a few perspectives I was able to learn about in the last couple of weeks that give you a sense of the diversity of viewpoints. The bottom line is we don't know how language evolved because we can't go back in time to observe and speak to our ancestors.

Sadly, our distant ancestors thousands of years ago were fucking terrible at documenting things. They also didn't have the highly productive habit of daily journaling. Otherwise, we could've pieced things together. What a bunch of inconsiderate pricks.

Even if we merge all these perspectives, it's not a stretch to say that language is a random collection of symbols and sounds that we have assigned some meaning to. Here are various definitions of language by scholars:

"Language is a purely human and non-instinctive method of communicating ideas, emotions and desires by means of voluntary produced symbols." (Edward Sapir, 1921)

"A language is a system of arbitrary vocal symbols by means of which a social group cooperates." (B.Bloch and G.Trager, 1942)

"From now on I will consider a language to be a set of sentences, each finite in length and constructed out of a finite set of elements." (Noam Chomsky, 1957)

"We can define language as a system of communication using sounds or symbols that enable us to express our feelings, thoughts, ideas and experiences." (E.Bruce Goldstein, 2008)

"Language is succinctly defined in our glossary as a human system of communication that uses arbitrary signals such as voice sounds, gestures, or written symbols. But frankly language is far too complicated, intriguing, and mysterious to be adequately explained by a brief definition." (Richard Nordquist, 2016)

Here's what Steven Pinker has to say about language:

Language fascinates people for many reasons, but for me the most striking property is its vast expressive power. People can sit for hours listening to other people make noise as they exhale, because those hisses and squeaks contain information about some message the speaker wishes to convey. The set of messages that can be encoded and decoded through language is, moreover, unfathomably vast; it includes everything from theories of the origin of the universe to the latest twists of a soap opera plot. Accounting for this universal human talent, more impressive than telepathy, is in my mind the primary challenge for the science of language.

What is the trick behind our species' ability to cause each other to think specific thoughts by means of the vocal channel? There is not one trick, but two, and they were identified in the 19th century by continental linguists.

The first principle was articulated by Ferdinand de Saussure (1960), and lies behind the mental dictionary, a finite list of memorized words. A word is an arbitrary symbol, a connection between a signal and an idea shared by all members of a community. The word duck, for example, doesn't look like a duck, walk like a duck or quack like a duck, but we can use it to convey the idea of a duck because we all have, in our developmental history, formed the same connection between the sound and the meaning. Therefore, any of us can convey the idea virtually instantaneously simply by making that noise. The ability depends on speaker and hearer sharing a memory entry for the association, and in caricature that entry might look like this:

What makes words offensive?

Before diving into why some words are offensive, let me give you a quick overview of the neural underpinnings of swearing.

I'm oversimplifying here, but articulate speech is predominantly controlled by regions in the brain's left hemisphere—specifically the frontal and temporal lobes, the prefrontal cortex, and so on. This side of the brain is responsible for word choices and grammar. Brain scans show increased activity in the left hemisphere when someone speaks.

Swearing, however, is different. It activates brain regions in the right hemisphere. When people swear, deeper, more ancient structures like the limbic system and basal ganglia are engaged. These areas are responsible for processing raw, emotionally charged expressions—like swear words and curses.

How do we know?

Aphasia, a terrible brain disorder that affects the language-producing regions of the brain, offers some clues. Patients with aphasia lose their ability to speak, but they can often curse fluently—even better than seasoned rappers and Bengaluru auto drivers.

Swearing aloud, like hearing the swear words of others, taps the deeper and older parts of the brain. Aphasia, a loss of articulate language, is typically caused by damage to the cortex and the underlying white matter along the horizontal cleft (the Sylvian fissure) in the brain's left hemisphere. For almost as long as neurologists have studied aphasia, they have noticed that patients can retain the ability to swear.

A case study of a British aphasic recorded him as repeatedly saying "Bloody hell," "Fuck off," "Fucking fucking hell cor blimey," and "Oh you bugger." The neurologist Norman Geschwind studied an American patient whose entire left hemisphere had been surgically removed because of brain cancer. The patient couldn't name pictures, produce or understand sentences, or repeat polysyllabic words, yet in the course of a five-minute interview he said "Goddammit" seven times, and "God!" and "Shit" once apiece. — From The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature by Steven Pinker

Similarly, Tourette's syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder affecting the basal ganglia, often involves involuntary verbal tics. About 10% of people with Tourette's develop coprolalia—a condition characterized by uncontrollable swearing:

Coprolalia shows off the full range of taboo terms, and embraces similar meanings in different languages, suggesting that swearing really is a coherent neurobiological phenomenon. A recent literature review lists the following words from American Tourette’s patients, from most to least frequent:

fuck, shit, cunt, motherfucker, prick, dick, cocksucker, nigger, cockey, bitch, pregnant-mother, bastard, tits, whore, doody, penis, queer, pussy, coitus, cock, ass, bowel movement, fangu (fuck in Italian), homosexual, screw, fag, faggot, schmuck, blow me, wop

Patients may also produce longer expressions like Goddammit, You fucking idiot, Shit on you, and Fuck your fucking fucking cunt. A list from Spanishspeaking patients includes puta (whore), mierda (shit), cono (cunt), joder (fuck), maricon (fag), cojones (balls), hijo de puta (son of a whore), and hostia (host, the wafer in a communion ceremony). A list from Japan includes sukebe (lecherous), chin chin (cock), bakatara (stupid), dobusu (ugly), kusobaba (shitty old woman), chikusho (son of a whore), and an empty space in the list discreetly identified as “female sexual parts.” There has even been a report of a deaf sufferer of Tourette’s who produced “fuck” and “shit” in American Sign Language.

— From The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature by Steven Pinker

Of course, this is a simplification. The relationship between speech, language, and brain regions is more nuanced than a simple left-hemisphere versus right-hemisphere dichotomy. Still, it's fascinating that swearing taps into the brain's older, more primitive systems.

Now, let me address the original question: what makes some words offensive compared to others? Isn’t it odd that words like "fuck" and "cunt" are considered more offensive than "murder" or "genocide"? We readily depict mutilation and decapitation in movies, but a single "fuck" can cause a strong reaction. Michael Shermer brilliantly describes this hypocrisy in a podcast:

My wife is from Germany, and she's constantly amazed by the American media's obsession with language or sex on TV. They'll show people getting blown to bits in war, with dead bodies and severed heads everywhere, and that's considered perfectly fine. But if a nipple is shown during the Super Bowl, it's 'oh my God,' or 'he used that word.'

Why?

If our words are just made up, what makes some words offensive compared to others? Rebecca Roache, the author of For F*ck's Sake, offers several compelling reasons in this thought-provoking article:

Swear words reference taboo subjects such as religion, sexual acts, and bodily functions.

Many swear words are blasphemous. While terms like "goddamn" or "Jesus Christ" may be more acceptable in secular societies, they remain deeply taboo in religious ones.

As philosopher Joel Feinberg notes, swear words "acquire their strong expressive power in virtue of an almost paradoxical tension between powerful taboo and universal readiness to disobey."

Some swear words, like "motherfucker," are offensive because they are directed at specific people, such as mothers. This personal dimension adds to the offense.

Swear words often have sharp and aggressive tones, and words like "fuck" and "cunt" are jarring to hear. We tend to feel a sting when we are on the receiving end and they feel like mental punches.

Swear words hit the part of the brain that processes negative emotions, as I mentioned above. As Steven Pinker says, "The most obvious thread is strong negative emotion. Thanks to the automatic nature of speech perception, a taboo word kidnaps our attention and forces us to consider its unpleasant connotations."

We all have social preferences, like how people should talk, walk, dress, etc., and swear words violate them.

Apart from these reasons, we have the usual complaints that swearing desecrates our sense of morality, corrupts the youth, and destroys the fabric of society, turning us all into vulgar lowlifes. While such old-fashioned views may seem ancient to people with liberal attitudes toward profanity, they are still pretty common.

But is this right?

There are two sides to this argument.

Words are just words

But words are words; I never yet did hear That the bruised heart was pierced through the ear. — William Shakespeare

Rebecca Roache articulates it beautifully: swear words are not magical sounds with innate offensive connotations—it's the context that makes them offensive:

Swearing, then, is as offensive as it is not because of some magic ingredient possessed by swear words but lacked by other words, but because when we swear, our audience knows that we do so in the knowledge that they will find it offensive. This is why context is important: there are some contexts in which we know we will not cause offence by swearing, and when we swear in such contexts our audience's knowledge that we did so without expecting or intending to offend helps ensure that we do not offend.

This explains why we are more tolerant of swearing by non-fluent speakers of our language, such as young children and non-native speakers, than we are of swearing by competent speakers. When non-fluent speakers swear, often we do not suspect them of doing so knowing that their words are offensive. Consequently, we are less likely to be offended.

The inimitable George Carlin again:

There are so many words you "can't say." Can't say fruit, can't say faggot, can't say Nancy boy, can't say pansy. Can't say nigger, boogie, jig, jungle bunny, molly, or schwartze. Can't say yid, heeb, kike, dago, guinea, wap, greaser, greaseball, spic, beaner, or PR. Can't say Mick, donkey, limey, frog, squarehead, kraut, Jerry, honky, chink, jack, nip, slope, zipperhead, gook—the list goes on.

But here's the thing: there is absolutely nothing wrong with any of those words in and of themselves. They're just words. It's the context that counts. It's the user, the intention behind the words, that makes them good or bad. Words are neutral. Words are innocent.

I get so tired of people going on about "bad words" or "bad language." That's bullshit. It's the context that matters. It's always the context.

Take the word "nigger." There is absolutely nothing wrong with the word itself. It's just a combination of sounds. The problem lies with the racist asshole using it. That's who you ought to be concerned about.

Think about it: we don't get upset when Richard Pryor or Eddie Murphy say it. Why? Because we know they're not racist—they're using it in a completely different way. Context. That's what makes all the difference.

Philosopher Ernie Lepore echoes this sentiment in the context of slurs:

I am not claiming that the speaker who tokens a slur term is blameworthy (or not), that any offense taken is warranted (or not). Nor am I claiming that the tokening was apt or inapt, necessary or gratuitous in achieving a particular point (whether it be rhetorical, pedagogical, artistic, etc.). These questions are downstream from the presence or absence of any offense effect. That is, first comes the offensive speech and then its moral assessment.

No one should deny that typical tokenings of slur terms can give rise to negative associations rooted in socio-historical, cultural, and psychological factors; these are open-ended, and so, not content-like. However, what I am claiming is that the trigger of these negative associations is not the word itself, but rather standard articulations of the word.

Note that on this proposal it becomes quite easy to account for the Hyper-projectivity Constraint. You cannot token a slur term without articulating it. But if I am right that it is standard articulations of slur terms which cause the offensive sting, then regardless of where that articulation occurs so does the potential to offend, even inside quotes or meaning attributions or even homonyms. And as far as meaning goes, as was illustrated above, we are able to deny any particular negative content without fear of linguistic incoherence because we are not appealing to meaning in order to account for an offensive sting. Indeed, for our purposes, slur terms may turn out be synonymous with their neutral counterparts.

Words hurt

On the other hand, one could argue that swear words force us to consider the unpleasant connotations, regardless of the context or articulation. In her delightful and brilliant book Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing, Melissa Mohr explores two aspects of words: their denotations (literal meanings) and their connotations (emotional and historical baggage). Here is a passage from her book:

Linguistically, a swearword is one that "kidnaps our attention and forces us to consider its unpleasant connotations," as Steven Pinker puts it. Connotation is a word's baggage, the emotional associations that go along with it, as opposed to its denotation, its dictionary definition. Cognitive psychologist Timothy Jay saw this distinction summed up in an exchange of graffiti on a bathroom wall. "You are all a bunch of fucking nymphomaniacs," one line read. Someone had circled "fucking" and added below, "There ain't no other kind."

The second writer chose to interpret "fucking" as a denotative use, not a connotative one. The literal definition is, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, "that engages in or is engaged in sexual intercourse." It can have many connotations, however, from "really bad" to "extraordinarily good." "Fucking nymphomaniacs" could be either, really—it is difficult to tell whether the tone is one of admiration or exasperation. Swearwords are almost all connotation—they carry an emotional charge that exceeds the taboo status of their referents.

One could also argue that since swear words are processed in the more primitive and emotional parts of the brain, their connotations bypass our perceptual filters and hit us with all their vivid and descriptive meanings:

If you're an English speaker, you can't hear the words nigger or cunt or fucking without calling to mind what they mean to an implicit community of speakers, including the emotions that cling to them. To hear nigger is to try on, however briefly, the thought that there is something contemptible about African Americans, and thus to be complicit in a community that standardized that judgment by putting it into a word.

The same thing happens with other taboo imprecations: just hearing the words feels morally corrosive, so we consider them not just unpleasant to think but not to be thought at all—that is, taboo. None of this means that the words should be banned, only that their effects on listeners should be understood and anticipated. — Steven Pinker, The Stuff of Thought

I guess there's something to this line of thinking. That said, I can't help but think of something that I heard the brilliant comedian Ricky Gervais say:

I've often said that people get offended when they mistake the subject of a joke for the actual target. They're not necessarily the same thing. You can joke about any subject—it all depends on the joke itself. There are no rules saying you can't joke about something. You can, you should, and you just can. Nothing is sacred.

Why do we swear?

Before I get to the why, it's impossible to talk about swearing without considering its peculiar characteristics. If you were a finger-wagging, self-confessed grammar Nazi, you would go mad trying to decode the syntactic and grammatical properties of profanity.

The maddening madness of swear words

American linguist John McWhorter captures this madness perfectly in his book Nine Nasty Words: English in the Gutter:

"Oh, jolly shit!" is funny first in that a woman—a mother, no less—was saying something with such a smutty feel in front of her kids but also in that it shows how our urge to curse often bypasses our fundamental instinct to make sense. What did "Oh, jolly shit!" mean, and if the answer is nothing, then why do we say such things?

"What the fuck is that?" is subject to similar questions—what part of speech, exactly, is fuck in that sentence? Profanity channels our essence without always making sense.

A few more illustrations from Steven Pinker's The Stuff of Thought:

As it happens, taboo expletives aren't genuine adverbs, either. Another "study out in left field" notes that while you can say That's too fucking bad and That's no bloody good, you can't say That's too very bad or That's no really good. Also, as the linguist Geoffrey Nunberg has pointed out, while you can imagine the dialogue How brilliant was it? Very, you would never hear the dialogue How brilliant was it? Fucking.

Most anarchically of all, expletives can appear in the middle of a word or compound, as in in-fucking-credible, hot fucking dog, Rip van Fucking Winkel, cappu-fucking-ccino, and Christ al-fucking-mighty—the only known case in English of the morphological process known as infixation. Bloody also may be infixed, as in abso-bloody-lutely and fan-bloody-tastic. In his memoir Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog, Dylan Thomas writes, "You can always tell a cuckoo from Bridge End . . . it goes cuck-BLOODY-oo, cuck-BLOODY-oo, cuck-BLOODY-oo."

One of my favorite examples of the grammatical anarchy of profanity comes from Holy Sh*t:

Connotation is a word's baggage, the emotional associations that go along with it, as opposed to its denotation, its dictionary definition. Cognitive psychologist Timothy Jay saw this distinction summed up in an exchange of graffiti on a bathroom wall. "You are all a bunch of fucking nymphomaniacs," one line read. Someone had circled "fucking" and added below, "There ain't no other kind." The second writer chose to interpret "fucking" as a denotative use, not a connotative one.

The other question we must wrestle with when thinking about profanity is: Where does the profanity in words come from? It's not as if the word "shit" came into being during the Big Bang with inherent fecal properties.

Words are social and cultural constructions—we endow them with meaning. A word becomes profane because we collectively decide that it’s “bad.”

How do we know this?

Research shows that people's physiological responses to swear words are stronger in their native language than in languages they learn later. This suggests that the emotional power of these words is deeply tied to the environment of our upbringing.

Benjamin Bergen, author of What the F, captures this idea perfectly:

Well it's demonstrably true that the only reason these words have power is because of how we treat them. A child who's punished for using a word or who sees caregivers avoid it in public is learning about the social rules governing rules. And those lessons are hard to unlearn. The word "fuck" wouldn't have the power it does if it weren't for all the people trying to get you not to say it.

— Benjamin Bergen, author of WHAT THE F

It’s remarkable that these words, which are nothing more than socio-cultural constructions, can have such a strong hold on us and evoke such a variety of reactions.

The beauty of vulgarity

Thinking about swear words, I couldn't help but marvel at the beauty of language. Despite being considered "bad" or abhorrent by many, they are still widely used.

Even more remarkable is their ability to express a vast range of emotions. We use swear words when we are angry, in pain, happy, disgusted, guilty, ashamed, frustrated, lonely, jealous, confused, terrified, nostalgic, sad, bored, and indifferent. It's also striking how varied the situations are—from individual experiences to social interactions—in which profane words can be used.

We often take the obvious for granted, and swear words are no exception. I curse like an uncultured degenerate, and yet until I started writing this post, I hadn't spent a moment thinking about the versatility of swear words, profanity, or whatever you want to call them.

With that said, let me get to the question at hand: why do we swear?

I like Steven Pinker's five reasons for swearing from this talk based on his book The Stuff of Thought.

Dysphemistic swearing

A dysphemism is the opposite of an euphemism. We use euphemisms to hide or soften the negative baggage of a word. But we use dysphemistic swearing to be intentionally blunt, harsh, or offensive.

Steven Pinker: There are times in life when the point of politeness has passed, and one feels the need to remind others just how disagreeable something truly is. For example, you might open your window and yell at someone, "Will you pick up your dog's crap?" Or recount an experience like, "The plumber was working under the sink, and I had to stare at the crack in his ass the whole time." Or imagine a wife snooping through her husband's email, saying, "So while I've been taking care of the kids, you've been sleeping with your secretary!" In these moments, the offense is intentional, and the English language offers us the means to express such strong emotions when necessary.

Abusive swearing

We sometimes use profanity as a weapon to abuse, intimidate, or humiliate others. In such moments, you reach for the strongest swear words because you need to convey the intensity of your emotion.

When someone bumps into you in traffic, you don't say "crap," you scream "motherfucker," or if you have the misfortune of having to drive in Bengaluru, then "gandu," "chooth," and "laude" tend to be at the tip of your tongue.

Steven Pinker: For example, you can liken people to effluvia and their associated organs and accessories when you refer to someone as a piece of shit, an asshole, or a dickhead. You can advise them to engage in undignified activities such as "eat shit," "shove it up your ass," or "fuck yourself." You can accuse them of having engaged in undignified sexual activities, and every undignified sexual activity has an obscene imprecation: incest as in "motherfucker," sodomy as in "bugger," fellatio as in "cocksucker," masturbation as in "jerk" and "wanker."

And my favorite comes from bestiality - a curse that was last used in 1585, but I suggest should be revived. The next time someone cuts you off in traffic, instead of using one of those hackneyed clichés, I suggest you advise the person to kiss the cunt of a cow, which would at least bring some fresh imagery to the situation.

Idiomatic swearing

This is the mildest form of swearing. We often use taboo words to convey context about a situation rather than the literal meaning of the word. For example, I use "my ass" heavily when I'm with friends and colleagues and need to say no or point out the absurdity or improbability of some assertion.

Idiomatic swearing uses words like "shit," "piss," and "fuck" in expressions that don't always make literal sense but serve other functions. Phrases like "shit out of luck," "get your shit together," "piss-poor," "pissed off," "my ass," "a pain in the ass," and "sweet fuck-all" rely on these swear words, yet it's puzzling exactly what those words are doing in these contexts. These words are used not for their direct meaning but for their ability to grab attention and shock the listener.

Swearing in this way also serves other social purposes. It can be a way to assert a "macho" or "cool" persona, or it might be used more casually among friends to express informality. In these settings, the use of swear words signals that you're in an environment where you don't have to censor yourself, creating a sense of ease or camaraderie.

Emphatic swearing

There are moments when we need to emphasize or call attention to something:

The taboo word is often used to draw a listener's attention, emphasizing the following noun or adjective. For example: "This is really, really fucking brilliant," or "He thinks he's a fucking scoutmaster, Rip Van fuckin' Winkle."

When emphatic and idiomatic swearing is overused, it can lead to a form of English sometimes referred to as "fuck patois." This is a style where swearing is so pervasive that it becomes almost a defining feature of the language. An example of this can be found in the story of a soldier who says, "I come home to my fucking house after three fucking years in the fucking war, and what do I fucking well find? My wife in bed, engaged in illicit sexual relations with a male!"

Cathartic swearing

Perhaps the most universal reason to swear: expressing pain, frustration, or anger. When you hit your finger while closing the door or stub your toe, you don’t pray to God; you let out a good and throaty fuck. In similar situations, animals react in fury and make a range of noises, but in humans, the language system is triggered.

The great sociologist Erving Goffman argued that cathartic swearing is not just an overflow of emotion; it's a form of communication. When someone swears in a cathartic way, they are signaling to a real or virtual audience that they are experiencing intense emotions—emotions so strong that they can't fully control them. Despite this, the act of swearing clearly conveys the specific emotion being felt.

In this context, swearing becomes a tool for expressing the depth of one's feelings, providing a kind of emotional transparency. It's a way of letting others know, "I'm overwhelmed, and this is how I'm processing it right now." This communicative function of swearing helps others understand the emotional state of the speaker, even if they don't directly articulate the emotion.

Apart from these five types of swearing that Pinker proposes, swearing performs a wide variety of roles. Swearing helps people express emotions and sentiments that ordinary language cannot:

The world-renowned expert in cursing, Timothy Jay, says that "there's a point where it's just more efficient to say, 'F*&^ you,' than it is to hit somebody. We've evolved this very efficient way to vent our emotions and convey them to others."

"Under certain circumstances, urgent circumstances, desperate circumstances, profanity provides a relief denied even to prayer." ―Mark Twain

Swearing serves numerous social functions:

It helps us bond. "You fucker" can be as much an endearing expression as an angry one.

Swear words are phenomenal icebreakers. If a room feels uncomfortable or stuffy to me, I drop a few fucks, shits and my ass, and things change in an instant.

Swearing is a subtle (or not-so-subtle) way of challenging authority. It's a way of saying you don't agree with the prevailing social norms or expectations of etiquette and decorum.

Swearing can also signify hierarchy. A dad or boss swearing can be a sign of authority and camaraderie, but kids or employees swearing can be seen as a sign of unruliness and insubordination.

This reminded me of something I heard on this brilliant Freakonomics podcast episode:

Stephen Dubner: As to the why, the purpose of swearing — and obviously, it differs from person to person, situation to situation — even I can think of a lot of different reasons. You might be angry. You might be disgusted. You might be trying to elicit humor from someone else. You might be trying to bond. You might be trying to show that you are your own person and I won't be bound by society's rules. If I ask you to give the answer to the title of this one book of yours, Why We Curse — why do we? How answerable is that question?

Timothy Jay: You just answered it. Stephen, you just elaborated a lot of the reasons why people swear. Now, we're the only animal with emotional architecture in the physiological that can express our emotions abstractly with words. I regard this as an evolutionary leap, that instead of fighting tooth and nail when we're angry with someone, we can say, "I hate you," or a variety of other words.

The other way of trying to understand the role of profanity is to look at it from an evolutionary lens. Most human features we have evolved over thousands of years due to evolutionary pressures, and language is no exception. If that is the case, then what evolutionary purpose does profanity serve?

This is the same question that cognitive scientist and podcaster Scott Barry Kaufman asked linguist John McWhorter:

Scott Barry Kaufman: I'm also just interested in the evolutionary origins of why curse words exist, in the sense that every language has profanity. I mean, it ticks the boxes in terms of something evolutionary—maybe a spandrel. I’ll say it's probably a spandrel, not an adaptation. But yeah, what is that? What is the spandrel of it? What’s the underlying human drive or human need? It’s a similar question to why every culture has religion. What function does that serve from an evolutionary survival or reproduction point of view?

John McWhorter: Well, I think… what do you think? I think, in terms of the spandrel, what happens is that you use something that started as a word in order to transgress, or to have certain things that are taboo. Because that’s part of what unites a society together: what things you consider taboo. And that kind of odd respect for those taboos. So yeah, the spandrel analogy is very apt. There is probably—though I haven’t checked all of them—no language where there aren’t things you're not supposed to say, but are said anyway. The only question is, what domain are those words going to cluster around? It depends on what horrifies or concerns the society.

So yeah, that's part of what it is to be human.

I asked ChatGPT to explain what a spandrel is:

A spandrel originally referred to the unintended triangular space formed by arches in architecture.

In evolutionary biology, the term was famously borrowed by Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin to describe traits or features in organisms that arise as incidental byproducts (or side consequences) of other evolutionary adaptations rather than as direct adaptations themselves. Just as the architectural spandrel is a structural leftover created by the placement of load-bearing elements, a biological spandrel is a characteristic that emerges not because it was specifically selected for, but because it is an inevitable outcome of how other evolved traits interact.

This makes sense. Profanity is a part of language, and while linguists, anthropologists, and psychologists have different theories on how and why language originated, there's reasonable agreement—not complete—that evolutionary pressures played a role. When you view profanity from an evolutionary perspective, it makes a whole lot of sense.

A brief history of swearing

Ordinary things often seem boring because of their familiarity. Take, for instance, the shirt or any garment you’re wearing. It might feel utterly unremarkable—it’s just a piece of cloth, right?

But if you take a moment and consider all the steps involved, from the cotton on the farm to the finished piece of garment, I can guarantee that your mind’s hole will be blown. The journey of a shirt starts with the planting of cotton seeds. Five months later, the cotton is harvested and ginned, cleaned, and then compressed into bales to be transported to textile mills.

The bales of cotton probably travel from one part of the world to a textile mill in another. The clean cotton fibers are then spun into yarn and dyed or woven into fabrics. Then the fabric is treated to clean it and improve the texture and feel. After all this, it's cut and sewn into the piece of cloth that's keeping you warm.

Behind something as unremarkable as a shirt is a fascinating journey that spans different parts of the world and hundreds of people. It's not just a damn shirt. Language, much like a shirt, is no different.

Those of us gifted with speech—many aren’t as fortunate—use words without much thought. It takes two seconds to tell someone to “go fuck themselves with a fruit peeler,” but those three words are the culmination of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of years of evolution.

When you pause and think about language and the ability it has given us to express our innermost thoughts and deepest emotions, you can’t help but have your mind’s hole not only blown but forcibly rammed and thrust with awe. The history of swearing, cursing, obscenity, filth, colorful language, uncouth utterances, gutter talk, or whatever you want to call it is no different.

Swearing dates back to the earliest moments when Homo sapiens and their ancestors in the genus Homo learned to make sounds. However, the problem with spoken words is that they don’t leave a tangible record. Unlike today, where we document every goddamn moment of our lives and broadcast it on social media, our ancestors were notoriously anti-tech.

So that means the history of swearing begins with the written word. A quick Google search tells me that the earliest evidence of profanity dates back 3,000–4,000 years to ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). We know of some funny and remarkably creative swear words thanks to the cuneiform clay tablets of the era.

Here’s one such example:

The next section of the preserved text is a parody of a menology, where for each month, the aluzinnu (a trickster or buffoon figure) humorously provides a menu, supposedly quoting a prescriptive original:

In Tasritu, what is your diet?

“Thou shalt eat spoiled oil on onions

And plucked chicken feathers in porridge.”

In Arahshamna, what is your diet?

“Thou shalt eat weeds in turnips

And … [text unclear].”

In Kislimu, what is your diet?

“Thou shalt eat donkey dung in bitter garlic

And emmer chaff in sour milk.”

In Tebitu, what is your diet?

“Thou shalt eat in butter the eggs of a caged goose,

Stored in sand and cumin infused with Euphrates water.”

In Sabatu, what is your diet?

“Thou shalt eat whole a jackass’ anus,

Stuffed with dog turds and fly dirt.

You won’t have worn out the teeth of a threshing board…”

That’s quite funny.

As I mentioned earlier, we don’t have the full oral history of swearing. Still, I like to imagine that, before the invention of language, our cave-dwelling ancestors had special sounds to tell someone to kiss their ass. They probably drew anatomical shapes on rocks—the earliest form of expressive art. The proto-fuck you might have sounded something like "ffkkuhh."

Roman obscenities: From streets to battlefields

I spent the last couple of weeks trying to learn about the history of swearing. In doing so, I came across Melissa Mohr and her wonderful book Holy Sh*t: A Brief History of Swearing. In the introduction of the book, she writes:

Swearing performs a crucial role in language today, as it did in the past; that alone makes it worthy of serious consideration and study. But swearing is also a uniquely well-suited lens through which to look at history. People swear about what they care about, and did in the past as well. A history of swearing offers a map of some of the most central topics in people's emotional lives over the centuries.

John McWhorter, the author of Nine Nasty Words, echoes this sentiment:

It's salty, but a society always is concerned about, or uncomfortable about, something. But I think if we get beyond those kinds of personal categories, it's going to be what concerns people and worries people and makes them uncomfortable.

This is a brilliant frame for thinking about the evolution of profanity, one that I hadn't considered until I started reading both books. The word fascinate itself comes from the Latin verb fascinare, meaning "to bewitch, enchant, or cast a spell on," deriving from fascinum, which referred to a "charm" or "bewitching influence."

The Roman notions about what was obscene and profane share many similarities with English:

Linguists generally agree that the worst words in English are the “Big Six”: cunt, fuck, cock (or dick), ass, shit, and piss. Ancient Latin had a “Big Ten”: cunnus (cunt), futuō (to fuck), mentula (cock), verpa (erect or circumcised cock), landica (clit), culus (ass), pedicō (to bugger), cacō (to shit), irrumo, and fellō.

Some of these words are very similar in English and Latin—cunnus and cacō are equally bad in both languages and used in similar ways. Some, such as futuō and landica, start to reveal some differences. Landica was a horrible obscenity in Latin, while clit is barely on the radar in English. And then there are words such as irrūmatio that English just doesn’t have, which point to ways in which the Romans were really different from us. The ancient Romans didn’t think about sexuality in terms of heterosexual or homosexual—they divided people up by whether they were active or passive during sex. This (to us) unusual schema gives rise to a very different obscene vocabulary.

The swear words mentioned above are in the order of the least offensive to the most. Before I give you a brief description of these Roman obscenities, there are notable differences given that Romans had a modern attitude towards sex.

Obscenities in ancient Rome had a different role than they do today. The Latin word for "obscenity" is obscenitas, though its etymology is unknown. It could mean filthy, unclean, inappropriate, immoral, or taboo. It could also refer to things that were of ill omen and would taint religious rites.

But certain obscene acts had religious significance and were thought to help religious rituals succeed. There were gods and goddesses related to obscenities like Priapus, the god of fertility who had a perpetually erect penis and was said to be pleased by certain obscenities.

Obscenities were also part of Roman festivals and ceremonies. Obscene songs and jokes were included in Roman weddings, believed to ward off evil and ensure fertility. Phallic imagery was openly displayed at weddings.

Bas-relief of a legged phallus ejaculating into an evil eye on which a scorpion sits, from Leptis Magna (Libya). — Wikipedia

There were also numerous religious ceremonies and festivals where people would either dress lightly or even be naked, and these events were filled with obscene dances and sexual jokes.

Most Roman cities were full of graffiti. We know this because the eruption of Vesuvius preserved some spectacular insults. Cunnus and cunt mean the same thing and were offensive in Rome then, as they are in English today. Much like the British today, the Romans put the word to spectacular use:

"Corus licks cunt" (Corus cunnum lingit)

"Jucundus licks the cunt of Rustica" (Iucundus cunum lingit Rusticae)

"It is much better to fuck a hairy cunt than one which is smooth; it holds in the steam and stimulates the cock" (Futuitur cunnus pilossus multo melius quam glaber / eadem continet vaporem et eadem verrit mentulam)

And perhaps my favorite involves a possibly jilted lover:

"Here I bugger Rufus, dear to ... :

despair, you girls.

Arrogant cunt, farewell!"

Mohr writes that caco, the Latin term for shit, was a vulgar term in Rome but not obscene. Barring the wealthy, most Romans used open and public toilets with no walls or curtains to shield their modesty. Some of these public toilets were massive, with up to a hundred seats:

There were also gigantic public latrines, called foricae, with up to a hundred seats. As the Roman Empire expanded, public latrines were seen as a mark of civilization, bringing sanitation to the masses. They were usually connected to a system of sewers that would carry the waste out of the city, solving the problem (in theory) of people tossing excrement into the streets. Latrines could be very grand, with marble seats, paintings on the walls, and a channel of running water near people’s feet to catch any urine that wasn’t aimed quite properly.

Futuo in Latin means fuck and is similar to the English word we put to such exquisite use. Despite its sexual connotation, it wasn't always an obscenity. It was simply the most direct word to refer to fucking.

Profanity could be put to spectacular use in politics and warfare. The Perusine War (41–40 BCE) was a civil conflict that erupted after the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE. The war was fought between forces loyal to the future Roman emperor Octavian against the forces loyal to Mark Antony and his wife Fulvia.

Glaphyra appeared to be a powerful lady at the Royal Court and was involved in internal politics in Cappadocia. Her powerful influence can be demonstrated by contemporary invective about the time of the Perusine War in 41 BC, by certain frank and famous verses which Triumvir Octavian composed about Antony. Antony had fallen in love with her. Allegedly Octavian wrote a vulgar squib about the affair, referring to Antony's wife Fulvia:

"Because Antony fucks Glaphyra, Fulvia has arranged

this punishment for me: that I fuck her too.

That I fuck Fulvia? What if Manius begged me

to bugger him? Would I? I don't think so, if I were sane.

'Either fuck or let's fight,' she says. Doesn't she know

my prick is dearer to me than life itself? Let the trumpets blare!"

The quoted excerpt below is even funnier. Imagine the dedication required to engrave bullets with insults about your enemies. That’s some next-level warfare right there:

The Latin word vagina, in fact, originally referred to the sheath of a sword. This connection between sex and violence was quite literal in the Perusine War. The opposing sides lobbed sling bullets at one another engraved with messages such as “Fulvia’s clitoris” and “Octavian sucks cock.”

Irrumo means to face-fuck or orally rape someone and was one of the most violent threats in ancient Rome. This was the Roman version of "suck my dick." It wasn’t just another run-of-the-mill obscenity. It invoked notions of violence and dominance, highlighting the prevailing notions of sex and power at the time.

The Romans were inclusive in the sense that they would sleep with both men and women, but they had peculiar notions about both sex and gender. All the vulgar words mentioned so far are from a male perspective. Men were active participants, as in, they could fuck. Women, on the other hand, were passive recipients, as in, they were fucked.

Notions of masculinity and virility were deeply embedded in Roman swear words. In ancient Rome, sex was as much about power and dominance as it was about love. The Latin word for man, vir, encapsulated these ideals. A strong vir was expected to sleep with both men and women, but what mattered most was his role in the act. To be considered a "real man," one had to be the penetrator, regardless of the partner's gender.

If a Roman vir was caught being penetrated, he would be labeled effeminate—less of a man. This explains why irrumatio was such a vulgar term. When Catullus, the poet of the late Roman Republic, had his poetry criticized for being too soft and effeminate, he clapped back by opening one of his poems with:

Pēdīcābo ego vōs et irrumābō

"I will fuck you in the ass and make you suck my dick."

This poem was so hardcore it wasn't even translated into English until the 20th century. I'm damn glad I live in the 21st century and can appreciate this literary banger.

The Roman senator Decimus Valerius Asiaticus faced a similar accusation of being a bit too "soft" and “girly” by Senator Publius Suillius Rufus. Asiaticus is said to have replied, Ask your sons if I am too "girly,” and they’ll tell you:

Tacitus, for instance, describes the reaction of the Roman senator Decimus Valerius Asiaticus, accused by Senator Publius Suillius Rufus of mollitiam corporis (literally "softness of the body" or sexual effeminacy): "'Question thy sons, Suillius,' he broke out; 'they will confess me a man!' "80 Asiaticus affirms his threatened masculinity by bragging of his prowess in penetrating his accuser's sons, again demonstrating that penetration—rather than the partner's gender—defined masculinity.

What a man, this Asiaticus.

Roman men who allowed themselves to be penetrated and were held in contempt were called Catamius and cinadeus. Such men were looked down upon and considered less than Roman. Both of these terms were derogatory insults that attacked a man’s masculinity.

Cinaedi were considered effeminate not only because of their sexual roles but also due to their mannerisms like excessive self-care, wearing makeup, grooming excessively, wearing female clothing, or engaging in traditionally feminine activities like spinning wool. This shows how times and tides change, but stereotypes remain the same.

The absolute worst way to insult a Roman man, however, was to accuse him of cunnum lingere—performing oral sex on a woman. The next worst insult was to call someone a fellator, or one who performed oral sex on men.

The Romans considered the mouth one of the most sacred parts of the body, and performing oral sex was thought to defile a person. It was considered worse than being penetrated. The belief goes back to Roman notions of sex as a way to assert masculinity. To the Romans, there was nothing masculine about performing oral sex. So in ancient Rome, to call someone a fellator was the ultimate insult. This foreshadowed why "cocksucker" was such an offensive word for the longest time.

One of the funniest anecdotes in Mohr's book is about penises. The Romans loved phallic symbolism, which makes sense when you consider that sex was an act of dominance. The Romans wielded their dicks much like swords:

Walking around in ancient Rome, one saw a lot of penises. There were erect penises sculpted, painted, and scratched over door frames, on chariot wheels, in gardens, on the borders of fields, in elaborate murals in reception rooms of fancy villas, hung around the necks of prepubescent boys. Even the Forum of Augustus, the center of Roman political and military life, was designed in the shape of an erection. Some scholars argue that it is an example of architecture parlante—a building whose form speaks to its purpose.

The forum was where military triumphs were celebrated, where law cases were argued, where boys came to put aside their childish clothing and assume the toga virilis, the garment that marked them out as full Roman citizens, as men. Something that today we see only in private was displayed prominently in public in ancient Rome.

Despite the ubiquity of dick pics, sculptures, and symbolism, mentula, the Latin word for penis, and verpa, which means a penis with its foreskin pulled back, were considered obscene and offensive.

Perplexingly, the obscene also had protective power. Victorious generals would be serenaded with obscene and vulgar songs to protect them. When Caesar returned to Rome after vanquishing the Gauls, he was mocked for being a cinaedus (cocksucker):

"Gallias Caesar subegit, Nicomedes Caesarem"

("Caesar conquered Gaul, Nicomedes conquered Caesar.")During Caesar's Gallic Triumph a popular verse began: "Gallias Caesar subegit, Caesarem Nicomedes," (Caesar laid the Gauls low, Nicomedes laid Caesar low), suggesting that Caesar was the submissive receiving partner in the relationship. It is unknown if a sexual relationship existed or was only a story told by his opponents, and Caesar vigorously denied its truthfulness. — Wiki

You may have noticed that I’ve used the terms swearing, cursing, obscenity, and vulgarity interchangeably. This is deliberate because that’s how we use them today. But in Rome and the Middle Ages, these words carried distinct meanings.

Despite the dual meaning of obscenity in ancient Rome, the negative meaning we ascribe to it comes from the Latin root obscēnus, which means "foul," "filthy," or "offensive."

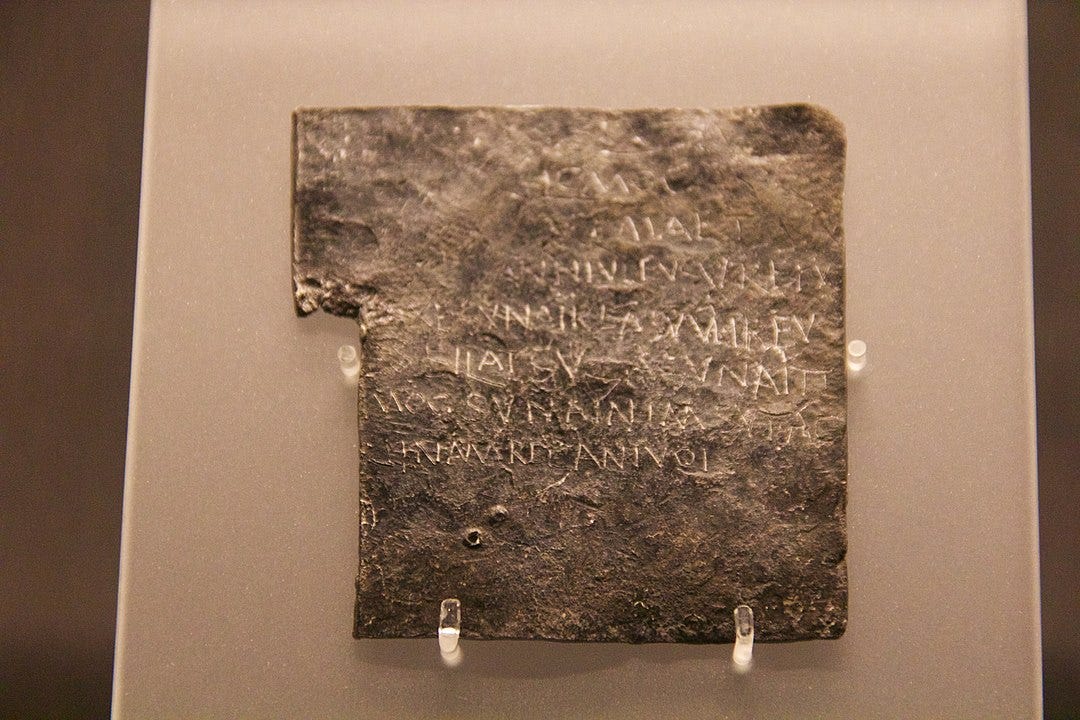

Cursing and swearing meant different things for the longest time. Cursing meant wishing ill upon someone. The ancient Romans wrote curses or pleas of justice on small tablets made of lead or tin called defixiones and cast them into wells, buried them in graves, and nailed them to tombs. This was a way to invoke the intervention of the gods and supernatural forces against perceived injustices.

Here’s one such defixione:

One of the 130 Bath curse tablets. The inscription in British Latin translates as: "May he who carried off Vilbia from me become liquid as the water. May she who so obscenely devoured her become dumb"

To get another taste of the use of obscenities and insults, one can look to the epigrams of the great Roman poet Martial:

Eat lettuce and soft apples eat: For you, Phoebus, have the harsh face of a defecating man.

Rumor tells, Chiona, that you are a virgin, and that nothing is purer than your fleshy delights. Nevertheless, you do not bathe with the correct part covered: if you have the decency, move your panties onto your face.

And these gems:

He’s quite well, Charinus, still he’s pale.

Hardly drinks, Charinus, still he’s pale.

A fine digestion too, Charinus, still he’s pale.

He takes the sun, Charinus, still he’s pale.

He dyes his skin, Charinus, still he’s pale.

Eats pussy, yet, Charinus, still he’s pale.

-

Chloe, I could live without your face,

without your neck, and hands, and legs

without your breasts, and ass, and hips,

and Chloe, not to labour over details,

I could live without the whole of you.

As we leave ancient Rome and its cornucopia of penises adorning it’s walls and citizens' necks, we now journey back further to biblical times to explore another crucial dimension of swearing—its religious origins.

The holy in the shit

You might wonder about the many meanings of swearing. To understand them, we have to look to religion and holy texts like the Bible. But it's not just the Bible—people have been swearing by the gods since time immemorial.

Here’s an oath from ancient Sumeria, where an Ummaite (a representative of the city) swore to Eannatum, king of Lagash, to respect territorial boundaries:

By the life of Enlil, the king of heaven and earth! The fields of Ningirsu I will eat (only) up to one karu, (and only) up to the old dike will I claim (as my right); but never unto wide eternity will I violate the boundaries of Ningirsu, nor will I infringe upon their (the boundaries') dikes (and) canals; nor will I rip out their steles. (However) if I violate (the boundaries), then may the shushgal-net of Enlil, by which I have sworn, be hurled down on Umma from heaven.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Gilgamesh swears by his divine parents before confronting the monster Huwawa:

Thoroughly aroused by this unexpected delay, Gilgamesh swears by his mother, the goddess Ninsun, and by his father, the divine hero Lugalbanda, that he will not return to Erech until he has vanquished the monster Huwawa, be he man or god. Enkidu pleads with him to turn back, for he has seen this fearful monster and is certain that no one can withstand his attack. But Gilgamesh will have none of this caution.

Oaths are central to the Bible. God calls Abraham to leave his wife and homeland, promising to make him the founder of a great city. Abraham is 75 and heirless, but being a believer, he takes God's word and begins his epic journey:

Go from your country, your people and your father's household to the land I will show you. I will make you into a great nation, and I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse; and all peoples on earth will be blessed through you.

At 75, Abraham is an old dude, and God is asking a lot. Given that Abraham is giving up his whole life, it’s only natural that he would have doubts. So God decides to assuage his concerns and tells him to bring some animals for sacrifice:

Bring me a heifer, a goat and a ram, each three years old, along with a dove and a young pigeon.

God instructs Abraham to cut the larger animals and arrange the pieces, sparing the birds. As twilight approaches, Abraham falls into a deep sleep and sees God:

When the sun had set and darkness had fallen, a smoking firepot with a blazing torch appeared and passed between the pieces.

The passing of the torch represents God making a covenant with Abraham. Later, God tests Abraham's faith by asking him to sacrifice his son Isaac. Abraham doesn't hesitate. He builds an altar, binds Isaac, and just when he is about to stab his son, God intervenes and reaffirms his promise:

By myself I have sworn, declares the Lord, because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, I will surely bless you, and I will surely multiply your offspring as the stars of heaven and as the sand that is on the seashore. And your offspring shall possess the gate of his enemies, and in your offspring shall all the nations of the earth be blessed, because you have obeyed my voice.

Since God is, well, God, there’s no one else for him to swear on—he’s the top dude, so he swears by himself. Animal sacrifice was a common way to make oaths back then, and God follows this tradition. The Bible contains many instances of God swearing on himself: “By myself I have sworn, declares the Lord,” “By My great name.”

God is also very detail-oriented. Right from the beginning, he gives detailed instructions on swearing. Here's one of the ten commandments:

Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain; for the Lord will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain.

Then he posts another divine clarification:

You shall not swear by my name falsely, and so profane the name of your God: I am the Lord. (Leviticus 19:12)

Scholars disagree that these were the earliest tweets, to which I say, fuck the scholars.

When you swear, you're essentially making God a witness and asking him to hold you accountable. If you break your promise, you're not only using his name in vain but also dishonoring him.

For supposedly being the holy book, the Old Testament contains its share of obscenities. When the Assyrian king Sennacherib was planning to conquer Jerusalem ruled by King Hezekiah, he sent his commander Rabshakeh to talk to King Hezekiah’s representatives. Rabshakeh used some rather some vivid descriptions to intimidate them:

But Rabshakeh said unto them, Hath my master sent me to thy master, and to thee, to speak these words? hath he not sent me to the men which sit on the wall, that they may eat their own dung, and drink their own piss with you? — (2 Kings 18:27)

Even God, whom the Bible is nominally about, sometimes uses obscenities to make a point that only profanity can. There is scholarly debate about what this passage means, but I have a feeling God is threatening to chop off Jeroboam’s dick:

Therefore, behold, I will bring evil upon the house of Jeroboam, and will cut off from Jeroboam him that pisseth against the wall, and him that is shut up and left in Israel, and will take away the remnant of the house of Jeroboam, as a man taketh away dung, till it be all gone. — (1 Kings 14:10)

But the New Testament isn’t so liberal. Here’s a passage from Paul’s letter to the Ephesians containing guidelines on how Christians must live:

But fornication and impurity of any kind, or greed, must not even be mentioned among you, as is proper among saints. Entirely out of place is obscene, silly, and vulgar talk; but instead, let there be thanksgiving. — (Ephesians 5:3–4)

Surely Paul was a hit at parties. But why is he so concerned about words? Melissa Mohr explains:

This is not so much because the words involved are themselves foul—greed, for instance, is not a bad word—but because saying the word leads to thinking about what the word represents, which can all too easily lead to action. Just as when God forbids people even to mention the names of other gods, lest they be inspired to worship them, the author of Ephesians seems to fear a chain reaction in which you mention fornication, then you begin thinking about fornicating, and pretty soon you're "fucking like any furious fornicator," in the immortal words of sixteenth-century Scottish poet Sir David Lyndsay.

The theory of language that motivates this fear is the same one that linguists and other scholars often use to understand swearing. Swearwords are thought to have a deeper connection to the things they represent than do other words; implicit in the Letter to the Ephesians is a similar claim about all words. In Ephesians, the link between word and referent is almost magical, so strong that merely saying a word seems almost inevitably to lead to the doing of the thing to which it refers.

Huh, that’s some magical thinking. One utterance of “fuck” and you’ll soon be fucking anything that moves like a rabbit? I’d bet a lot of people wish obscene words had this genie-like ability.

These Christians aren't fucking around. They were serious about people like me who use vulgarities without a care in the world. They have passages in the holy book to scare us shitless. Here's Jesus himself:

I tell you, on the day of judgment you will have to give an account for every careless word you utter; for by your words you will be justified, and by your words you will be condemned. — (Matthew 12:36–37)

Oh Christ!

Shit, did I do it again?

Fuck!

Good lord! Nooo!

I guess I've booked myself an appointment in hell.

The New Testament’s prescriptions on the language that people could use had a profound impact on what was considered obscene.

From Gropecuntlane to Fuckinggrove:

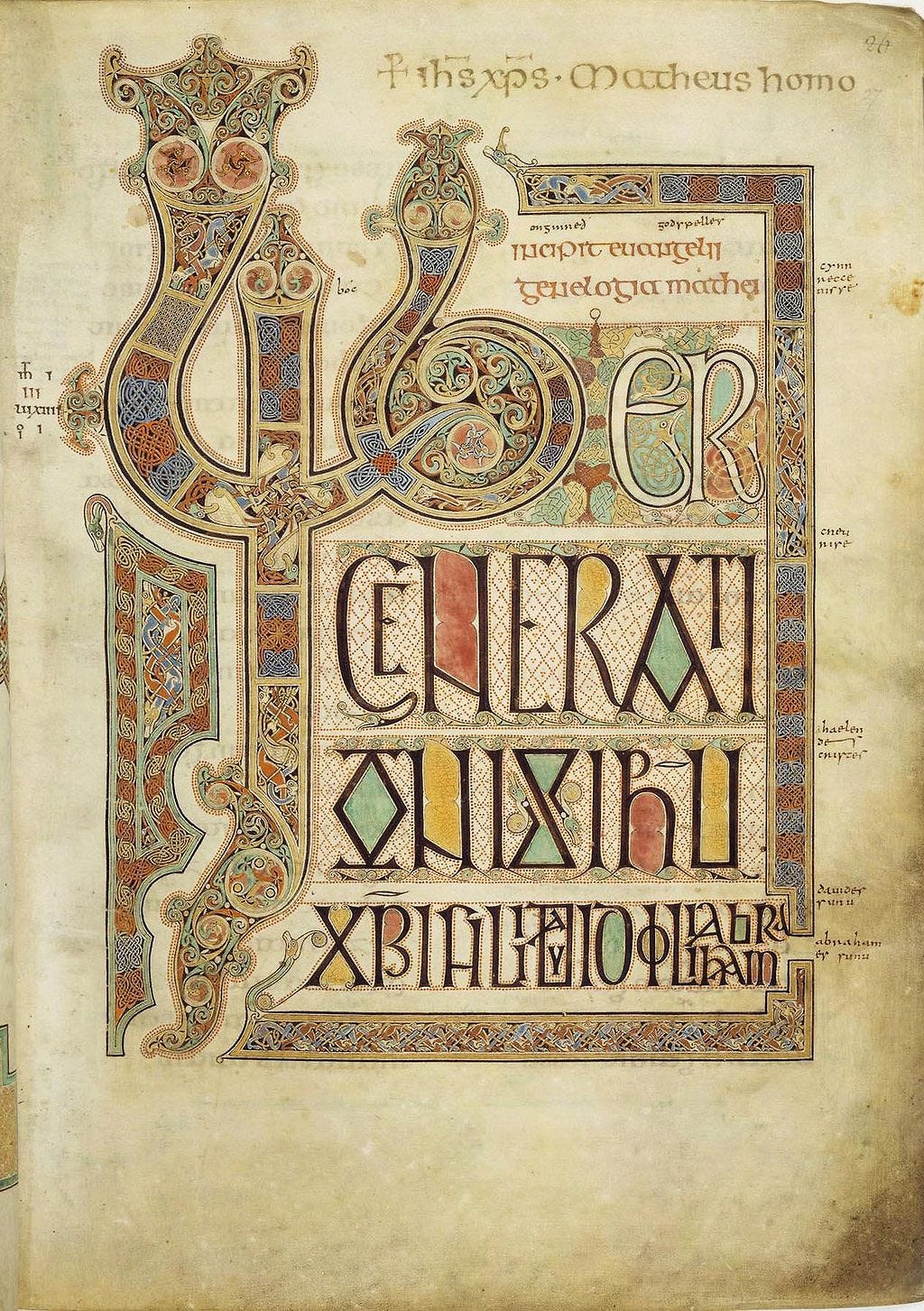

This beautiful image depicts a page from the Lindisfarne Gospels, which contains the four Gospels of the New Testament. It is said to have been created around 715 CE by a monk named Eadfrith and written in Latin.

I asked OpenAI’s Sora for a video of Eadfrith working on the manuscript:

Goddamn! AI be so good!

Some 250 years later, Aldred, who stayed at the Lindisfarne Abbey, translated the original Latin manuscript into Old English. As he’s translating, he gets to Matthew 5:27, which reads, “Ye have heard that it was said of old time, Thou shalt not commit adultery.” Aldred translates this as:

“You have heard that it was said to them of old, don’t sin, and don’t sard another man’s wife.”

Now, "sard" today refers to a brownish-red gemstone. But in the Middle Ages, it meant fuck. This isn’t an isolated example of an obscenity from the holy. There are plenty of colorful descriptions that today would be considered obscene:

“A geldynge, þe ballogys brusyd or kut off, & þe ʒarde kut awey, shal not goon yn to þe chirche” (Deut. 23:1) (a gelding [eunuch], the bollocks bruised or cut off, and the yard [penis] cut away, shall not go into the church). The same constraint went for sacrificial animals: “Ye shall not offer to the Lord any beast whose bollocks/balls [ballokes] are broken” (Lev. 22:24). In American English, balls is not a polite word, but it is not a particularly bad one. In Britain, however, bollocks was and is quite obscene. In a 2000 ranking of the top- ten swearwords by members of the British public, bollocks came in eighth.

My favorite:

“The Lord will smite you with the boils of Egypt [on] the part of the body by which turds are shat out” — (Deut.28:27).

“the Lord … smote [the people of] Azothe [Ashdod] and its coasts in the more private/secret part of the arses” — (1 Sam. 5:6)

Now, the use of words like “arse,” “turds,” “balls,” and “sard” in the Bible might seem surprising to us today. But for people in medieval England, these weren’t considered particularly shocking. In fact, much more explicit language was common in everyday speech:

Shiterow was the common name for a heron, a freshwater bird.

Windfucker was a colloquial term for the kestrel, a type of falcon.

Cuntehoare seems to have referred to a type of bird.

Pissabed was a nickname for the common dandelions.

Arse-smart referred to water pepper, a plant that grows in damp places and shallow water.

Open-arse was the name for the the medlar tree.

Pisse-mires meant ants.

The fun with medieval English doesn’t stop there. In 13th-century London, there was a street called “Gropecuntelane,” which, as the name suggests, was associated with prostitution. There were also several Shitwell Ways and Pissing Alleys. In medieval Bristol, there was a glade called Fuckinggrove.

Things get funnier when it comes to the names of people. Mellissa Mohr documents a Randall Shitboast, Thomas Turd, and Thomas Bastard. Perhaps my favorite people from medieval England were Gunoka Cuntles, Bele Wydecunthe, Godwin Clawcuncte, and Robert Clevecunt.

In Nine Nasty Words, John McWhorter writes about Roger Fuckbythenavel, Henry Fuckbeggar, and Simon Fuckbutter. Henry Fuckbeggar wasn’t a commoner but part of Edward I's retinue. If this tweet is accurate, he may have been responsible for looking after the royal horses, along with Walter Fucket.

What a fucking amazing duo.

And just to be clear: all those names from the 1200s and 1300s were real—I didn’t make them up.

Here are some brilliant sentences from vulgaria, textbooks of practical Latin designed to help learners as young as seven translate between Latin and English:

Stanbridge’s text continues with a variety of phrases a schoolboy needs to know, presented in seemingly random order: “I am weary of study. I am weary of my life… . I am almost beshitten. You stink… . Turd in your teeth… . I will kill you with my own knife. He is the biggest coward that ever pissed.” Clearly Stanbridge chose topics that would interest young boys, but he is not trying to pique their interest by using bad words.

Sure, these words were vulgar, but in Middle English, "vulgar" simply meant "common" or "ordinary," not what we understand it to mean today. For example, cunt, one of the most shocking and obscene words in modern English, was once the most direct word for the vulva and appeared in medical texts. Here’s a casual reference from a 14th-century surgical textbook:

Something to note here is that the word appeared in a legal document. For a long time fuck was not considered especially vile. Cunt, too, was once an ordinary word. A fourteenth-century surgery textbook calmly states that “in women the neck of the bladder is short and is made fast to the cunt.”

So, if words like "shit," "piss," "arse," and "cunt" were everyday words in medieval England, how did people insult each other? Melissa Mohr's research shows that accusations of thievery, marital infidelity, and dishonesty were far more serious insults. Words like "harlot" (originally meaning vagabond), "whore," "whoreson," "whoremonger," and "cuckold" were common insults.

One explanation for why shit, piss, arse, and cunt were considered ordinary at the time is that there was no concept of privacy as we know it today. Houses at that time typically consisted of one large hall where people cooked, ate, slept, and also relieved themselves. Toilets, as we know them, didn’t exist, and people openly defecated and urinated.

Nudity was also common. Most houses had a multi-purpose hall, but some houses would have a separate room for the lord and the lady. Servants slept in these same chambers of the lords and ladies available at quick call. This meant that they saw a fair amount of people fucking.

Since people spent their entire lives under the same roof without privacy, bodily parts and excremental actions didn’t carry the same sense of taboo they do today. Witnessing someone defecate in the open or observing sexual activity was as commonplace as greeting someone named Gunoka Cuntles, watching a Windfucker fly overhead, or taking a leisurely stroll and casting a yearning glance toward Gropecuntlane.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that these words couldn’t be used as insults. In the book, Melissa Mohr’s refers to the great Chaucer’s use of obscenities. So I asked ChatGPT to give me the best of Chaucer’s vulgarities, and they are spectacular.

This is from The Millers Tale in which Absolon is tricked by Alison into kissing her ass:

The night was dark as pitch, or as coal, And at the window out she put her hole, And Absolon, he fared no better nor worse, But with his mouth he kissed her naked arse Most savoringly, before he was aware of this. He started back, and thought something was amiss, For well he knew a woman has no beard. He felt a thing all rough and long-haired, And said, 'Fie, alas! What have I done?

Another one that would’ve gotten him cancelled in 2024:

Middle English

And prively he caughte her by the queynte,

And seyde, ‘Ywis, but if ich have my wille,