Revolution in a box: The extraordinary story of the ordinary shipping container

The story of the shipping container—Part 1

Can you think of some of the greatest inventions and innovations in human history?

I’m sure you thought about things like the printing press, steam engine, and electricity. Sure, these innovations permanently altered the course of human progress. But what if I told a simple box was just as consequential in tilting the arc of human progress upwards?

If you asked 10 people the same question, I’m 100% sure that 9 out of 10 people wouldn’t think of the shipping container. But the humble steel box has played as big a role as anything in changing our lives for the better.

I did my MBA internship in a company called Giftxoxo sometime around 2014, I think. Back then, they specialized in corporate gifting—those cheap diaries and mugs that your manager so generously gives you so that you don’t quit😜. Their business model was simple. If Infosys wanted 1000 branded hoodies, they’d find a vendor, get the hoodies customized, and resell it at a markup.

The manager I reported to was a brilliant guy and he handled procurement. His job was to find the fastest and the cheapest vendors for a given item. On any given day, he would have multiple orders. He’d search for items, haggle with vendors, procure items, get them customized, and deliver across India while sitting in an office in Indiranagar—It was fascinating.

A few years later, a friend and I tried the same business. It flopped miserably, but we still managed to fulfil a few orders. I remember going to Avenue Road to get a few diaries customized and selling them to some startup—we made a decent profit. That was the first time I appreciated the world of logistics, and I’ve had a passing interest in it ever since.

If you’ve accidentally paid attention to the news, you might have heard about the global supply chain crisis. The only time most “normal” people used the phrase “supply chain” was when they had to mug up this nonsense to pass exams in MBA. Remember the bill of getting laid?

Or was it a bill of lading?

Please don’t ask me the name of this subject. MBA is a traumatic phase of one’s life, and I don’t want to regress to a state where I go back to saying “synergy” 30 times a day.

Anyway, you might have read about the massive shortages of goods and clogged ports. It’s a global issue and pretty much everybody from companies to pets have been affected. Given that I’m jobless, I’ve been keeping some tabs on this crisis.

The reason for this whole pointless Kannada movie-style flashback is that I came across this old but brilliant piece in the Nautilus about shipping containers. I knew a bit about surface logistics but nothing about ocean shipping. As I was read the piece, I was amazed at the profound impact of shipping containers on the world. It’s all the more shocking considering the fact that it’s just a dumb metal box—no fancy technical wizardry.

It’s stunning just how integral this box is to our lives, and I wanted to learn more. So I’ve been doing some Googling over the past few weeks. The history of the shipping container is absolutely fascinating. Everything we eat to wear at some point spent some time on shipping containers. Container ships and shipping containers are the circulatory systems of global trade.

When we have a mild heart attack, we collapse. But when global shipping has a heart attack, factories stop, prices of goods shoot up and entire economies suffer.

Remember the Ever Given? It was a 400-meter ship with over, 18000 containers that got stuck in the Suez Canal in March 2021. The Suez Canal is a vital artery of global trade—12% of all global trade flows through it. Ever Given was stuck for a week and at one point over 350 ships with hundreds of billions of goods were blocked, throwing a wrench into global trade.

For the first time, shipping became a meme and entered mainstream consciousness.

Otherwise, the only thing I remembered about ships is this iconic scene from Pirates of the Caribbean.

The simple box has revolutionized the world, so much so that Human Progress named Malcom McLean, the father of container shipping, one of the Heroes of Progress. Forbes Magazine called Malcom McLean “one of the few men who changed the world.”

These two excerpts are perhaps the best descriptions of the shipping container:

Think of the shipping container as the Internet of things. Just as your email is disassembled into discrete bundles of data the minute you hit send, then re-assembled in your recipient’s inbox later, the uniform, ubiquitous boxes are designed to be interchangeable, their contents irrelevant. —Nautilus

Ocean shipping is the biggest real-time datastreaming network in the world. —Wired

The history of contemporary shipping began on April 26th, 1956, when the Ideal X, an old modified World War II T-2 oil tanker, sailed with 58 33ft aluminium truck bodies from Port Newark, New Jersey, to the Port of Houston, Texas. The brain behind this operation was Malcom McLean—the father of containerization.

As the Ideal X sailed, Malcom McLean walked up to a couple of people watching and asked them what they thought, without revealing that he owned the ship. Freddy Fields, a top official of the longshoremen’s association, reportedly said, “I think they ought to sink the sonofabitch.”

Maybe he knew, maybe he didn't, but Malcom McLean had just changed shipping forever. He had just unleashed a revolution that would alter global trade and the global economy in unimaginable ways. With that maiden voyage, he had just unshackled the ravenous animal spirits of globalization and unleashed the long boom. The modern history of shipping didn’t begin with a bang, but a son of a bitch dialogue!

The story of Malcom McLean is an incredible rags-to-riches story. He was born in 1913 in North Carolina to a typical family that wasn’t rich but managed to get by. Malcom was exposed to entrepreneurship from a young age. His first job was selling eggs from his mom for a commission. After graduating from high school, he started working in a grocery store in 1931 at the depths of the great depression.

But the story really began when he started managing a gas station. He figured he could make five bucks by shipping oil and told the station manager he could do it—the manager agreed. Malcom was barely in his 20s at this point. The station manager lent him an old rusty trailer, and so began Malcom McLean’s trucking empire. By 1934, he had saved enough money to buy another truck for $120 and hired a driver. He started transporting dirt for the government, and he was still able to save some money after paying the driver.

Maxton, North Carolina, was a farming community without proper transport. Malcom bought another truck with the savings to transport vegetables. By the age of 22, he already owned a few trucks.

By 1940 he had 30 trucks and had revenues of over $230,000. By the 1950s, he had between 600 and 1770 trucks based on various accounts, 2000+ employees, and 37 trucking terminals. The McLean trucking company was the 5th largest trucking company in the US with $12 million in revenue.

The two defining traits of Malcom were his audaciousness and his eye for detail. He was constantly searching for things that could make things efficient—this was one big reason why he had better margins than his competitors. One example of this relentless pursuit to be better was roughening (crenelating) the sides of truck trailers to reduce wind resistance, which meant increased the fuel efficiency of his trucks. He also took immense risks by borrowing heavily. By the 1950s, he already had millions in debt. That wouldn’t be the last time he borrowed, either.

But thanks to the dramatic World War 2 spending in the 1940s and the ensuing economic boom, there were nearly 9 million trucks on the roads from a million in the 1920s. By the 1950s, the traffic was getting worse, and the roads weren’t built to handle the traffic. Around this time, several states had started to impose tolls on out-of-state trucks and weight restrictions, making it hard to do business.

Pre-containerization, shipping was called breakbulk shipping and the ship itself was a shipping container. Breakbulk was slow and tedious. Every individual item had to be shipped on a truck or train and stored at the dock warehouses. Each item had to be manually loaded onto the ship by dockworkers and had to be stored in the several levels of empty spaces below the decks.

Ships used to transport thousands of items; some of the large ships would even transport up to 200,000 items.

This was incredibly costly, time-consuming, and risky. A good chunk of the goods used to get damaged and theft at ports was a huge issue.

Theft and pilfering were widespread that there was a joke:

“twenty dollars a day and all the Scotch you could carry home”.

Ships would often spend up to two-thirds of their transit time on ports.

The story Malcom McLean told was that he had the lightbulb moment for a shipping container when he had to wait hours to unload the cotton bales he was transporting. He thought, why load and unload everything and why not transport the entire truck on a ship:

I had driven my trailer truck up from Fayetteville . . . with a load of cotton bales that were to go on an American Export ship tied up at the dock. For some reason or another, I had to wait most of the day to deliver the bales, and as I sat there, I watched all those people muscling each crate and bundle off the trucks and into the slings that would lift them into the hold of the ship. On board the ship, every sling would have to be unloaded by the stevedores and its contents put in the proper place in the hold. What a waste in time and money! Suddenly, the thought occurred to me: Wouldn't it be great if my trailer could simply be lifted up and placed on the ship without its contents being touched?'

Marc Levinson, the author of The Box, the definitive book on the history of the shipping container thinks Malcom made up of the story for the press. He says Malcom had the idea for the shipping container much later in his life.

The shipping container wasn’t an invention as much as an innovation. I mean, it’s just a box. Containers have been used in some form or the other for centuries. You can trace the usage of some form of standardized containers to the Mediterranean basin going back 5000 years. The Greeks and the Roman used ceramic containers called Amphorae to transport wine, oil, nuts, and herbs going as far back as the 3rd century BC.

There were several precursors to the modern shipping container in the early 1990s in Europe and the US, but they were very limited. Both shippers and railway companies had some version of containers. In the 1940s, the US army had started using small containers called CONEX boxes. They were 8 ft 6 in long, 6 ft 3 in wide, and 6 ft 10 in high. The White Pass and Yukon Corporation of Canada, a railway company, had built its own ship for coastal shipping small 8’ x 8’ x 7’ sized containers. It was one of the first relatively large-scale container operations.

The revolution begins

By the 1950s, Malcom McLean had two problems:

The rising traffic, congestion, and poor road infrastructure

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) regulated trucking and rail, and it set the rules for pricing, etc. Malcom had several run-ins with the ICC when he wanted to reduce prices and had been fined for weight restrictions.

Given the issues with rising traffic and regulations, Malcom saw shipping as the solution. His vision was to integrate both trucking and shipping and provide seamless service. By 1955, Malcom had come across a company called Waterman Steamship Corporation, and it had a subsidiary called Pan-Atlantic Steamship Corporation, which had 16 routes from Boston to Houston. The problem was that the ICC didn’t allow ownership of both trucking and shipping.

To get around this issue, he moved the ownership of McLean Trucking to a trust controlled by his family. He immediately took control of Pan-Atlantic, the subsidiary of Waterman. His competitors complained to the ICC, but by then, he had sold off the entirety of McLean trucking for anywhere between $6-14 million.

He later acquired Waterman itself in what was probably one of the first leveraged buyouts (LBO). He took a $42 million loan, acquired Waterman, and used the cash on Waterman’s books to pay the loan back.

Again, to reiterate how bold he was before the acquisition, Waterman was a debt-free company, but it had $22 million in debt post the acquisition. He later realized that lifting entire trucks onto ships with their wheels was pointless, and detaching their trailers was the best way to go about it. He bought two World War II oil tankers from the Govt for cheap and modified them to carry the truck trailers detached from their chassis and wheels. Malcom figured if this didn’t work, he could use the tankers to carry oil.

With the help of Keith Tantlinger, an engineer at Brown Industries, he figured 33ft aluminum containers would work for the maiden voyage. They were several other issues, but by 1955 McLean was ready to sail, but they had to delay to convince the ICC and the coast guard. But finally, after much drama, the Ideal-X set sail on April 26th, 1956, and so began the containerization revolution.

Revolution delayed

The revolution would take a few more years to take hold. Shipping containers were obviously a good idea, and they were steadily proliferating. But the problem was that people in both the US and Europe had their own dimensions, and there was no standardization. Some containers were 7ft wide in Europe and 8ft in the US. If everybody had their own dimension, multimodal shipping—using the same container on boats, trucks, and railways—wouldn’t be possible, and containers would never become mainstream.

Soon, the United States Maritime Administration and Federal Maritime Board, which regulated the maritime industry, got involved in 1958 to set standards with the Navy’s support. After a while, the American Standards Association, an industry body, and The National Defense Transportation Association, also got involved. In 1961 the International Standards Organization (1S0) got involved, and it was an all-out battle to set the standard.

It was 1962, and along with the dimensions of the container, there was also a battle brewing over corner fittings. These were steel weldings meant for loading containers and locking them on truck chasing. All shipping companies, including Malcom McLean’s Sea-Land, had their own patented corner fittings, and they all were lobbying to impose their standard because royalties were at stake

Keith Tantlinger, the engineer who designed the first container that sailed on Ideal-X had designed Sea-Land’s patented corner fitting. He convinced Malcom to release the patents to break the deadlock. Malcom saw the bigger picture and released Sea-Land’s patents. It took up until the 1970s for the standards on the dimensions of containers to be agreed upon after hundreds of committees, back-alley deals, and fights in congress.

Eventually, 20 ft and 40 ft containers became the standard across the world.

Now that the containers were standardized, they could easily be shipped on boats, trucks, and trains without the need for any modifications. Standardization is what really led to shipping containers becoming the operating system of global trade. This was Malcom’s greatest contribution.

No wonder Forbes Magazine called Malcom McLean “one of the few men who changed the world.”

Containers were steadily becoming popular but still had a small share of trade.

The Vietnam War

By the 1960s, the US had already been waging war in Vietnam, albeit in a limited capacity. But in 1965, there was a massive troop build-up, and the US Army was shipping a vast amount of military gear, food, and aid to Vietnam. The problem was that Vietnam barely had any ports and the infrastructure needed for shipping.

Goods being shipped into Vietnam were clogging up makeshift ports. They were just sitting at the ports, and the Army wouldn’t even know. This soon became a media scandal.

Malcom McLean spent an insane amount of time and energy to convince the US Army that he could solve the problem with containers. After years of convincing, and cajoling, he won a $70 million contract. He soon built a port at Cam Ranh Bay, and the logistics issues improved dramatically in Vietnam. The US Army soon became Sea-Land’s biggest customer with about $450 million in revenues, accounting for 30%-50% of Sea-Land’s business.

The birth of globalization

Sea-Land was shipping full containers to Vietnam but was sailing back empty, but the Army was paying for both the legs of the journey. So Malcom thought, why not make an extra profit. By the late 60s, Japan was quickly becoming the biggest consumer electronics manufacturer in the world. On the way back from Vietnam, Malcom McLean’s ships started exporting electronics to the US.

This was when containerization went global.

Containerization arguably kickstarted globalization by shrinking the world and reducing transportation costs. By some estimates, containerization has reduced shipping costs by as much as 90%.

The effects of containerization have also been measured by the reduction of transport at ion costs across the globe. For example, controlling for fluctuations in fuel costs, Hummels (2007: 142) provides a con servative estimate that the price of bulk shipping, measured in real dollars per ton, is roughly half than it had been in 1960, and a third of its price in 1952. However, Levinson ( [ 2006 ] 2016) estimates that the decline in shipping costs was much larger. Whereas the cost of shipping cargo was roughly $5.83 per ton in 1956, on the maiden voyage of the first container ship, McLean’s Ideal-X, the cost of shipping cargo was merely $0.16 per ton (Levinson [2006] 2016: 68).

Without the shipping container and the dramatic reduction in transport costs, it’s hard to imagine today’s globalized world.

Daniel M. Bernhofen, Zouheir El-Sahl, and Richard Kneller analyzed the impact of containerization. Their conclusions were stunning:

Looking at 22 industrialised countries, it found that containerisation was associated with a 320% increase in bilateral trade over the first five years and 790% over 20 years. A bilateral free-trade agreement, by contrast, boosted trade by 45% over 20 years, and membership of GATT raised it by 285%. In other words, containers have boosted globalisation more than all trade agreements in the past 50 years put together. Not bad for a simple box. — Economist

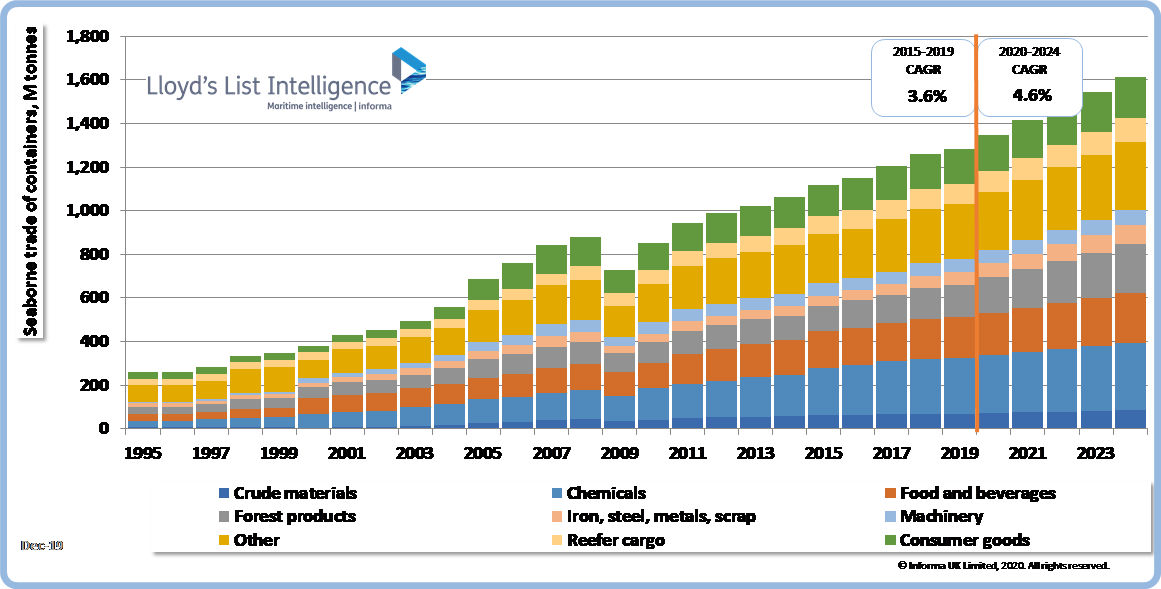

Trade cost is a broad measure that includes everything from tariffs, freight, communication to distribution costs. 20% of the fall in trade costs came after 1960. The 2nd image shows the cost of shipping dry bulk such as oil, coal, and ore. It’s been on a steady downtrend since 1850-60. You can extrapolate that to container costs.

The abstract of this book goes as far as to say that globalization would’ve been a pipe dream without the shipping container:

This book maintains that container shipping is vital to the actualisation of globalisation, and that without it, globalisation would remain a concept rather than reality.

At the very least, the shipping container has an outsized impact on shrinking distance across countries and enabling low-cost trade.

Check out this stunning visual of global shipping to get a sense of the scale:

Globalization unleashed

Without containers, we probably wouldn’t have seen this dramatic growth in trade.

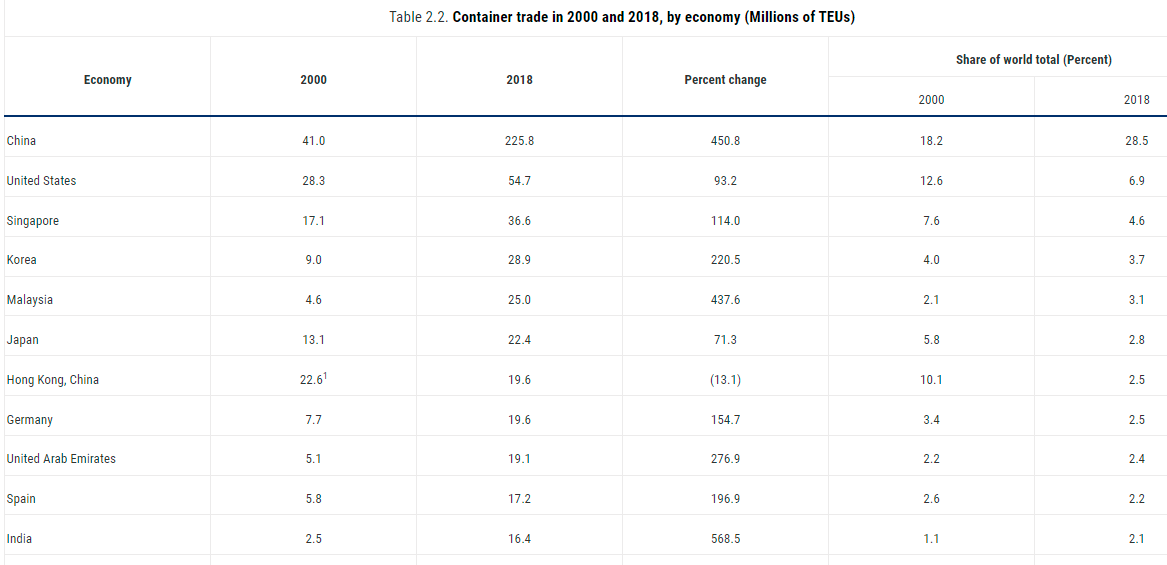

We probably wouldn’t have seen the rise of China, and we probably wouldn’t be enjoying all the cheap goods we enjoy today. Containers dramatically shrunk the price of per-unit costs from a few dollars to cents. To imagine that we can import a few 100 t-shirts from China for peanuts—that’s stunning.

Global supply chains

Here’s a map of all the shipping routes and ports.

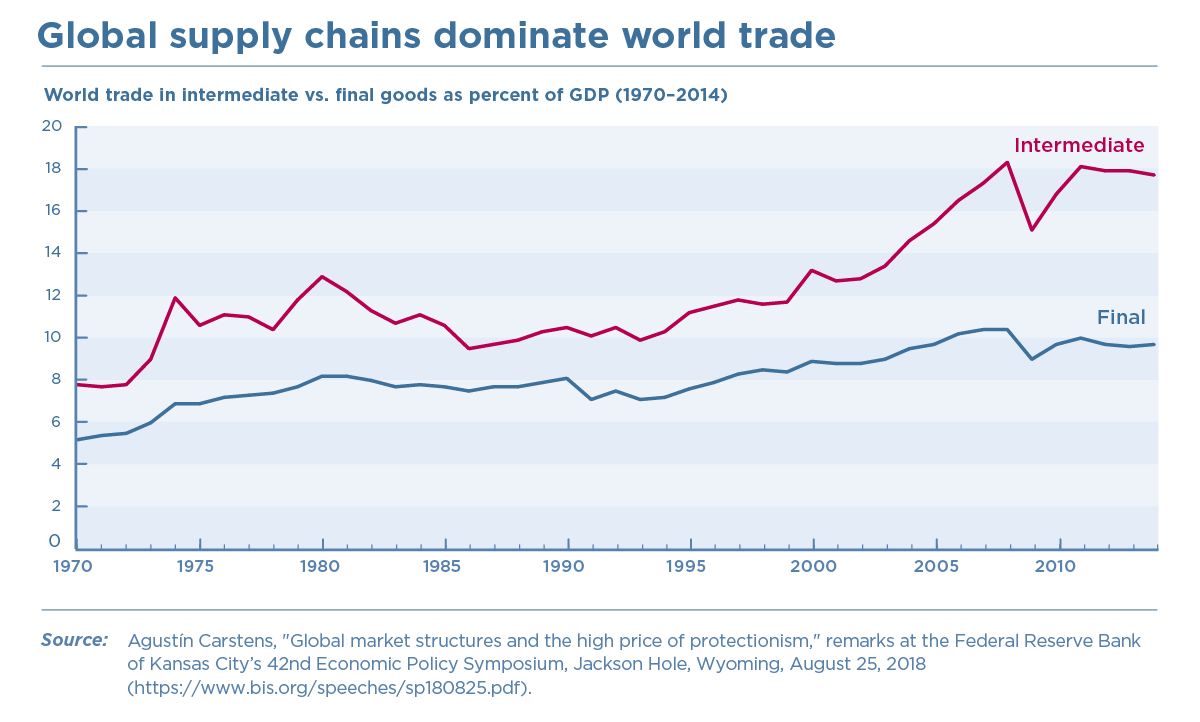

The shipping container, by dramatically reducing shipping costs, has enabled sprawling and mind-bendingly complex global supply chains. For example, an Apple iPhone has components from 43 countries across 6 continents. The supply chains of auto manufacturers are even mind-blowing. Ford has over 11,000 suppliers across 40 countries.

Containerization enabled Just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing, and it made the old-school style of having high inventories obsolete. Thanks to cheap shipping costs, manufacturers could maintain lean inventories and order goods as needed, which increased margins and reduced inventory costs.

Before containerization, manufacturers used to be mostly situated alongside ports because it made importing raw materials and shipping finished goods easier. But containerization made it possible for manufacturers to move anywhere and enabled the diffusion of industry. They could move where the land and labor are cheap. Containers led to the rise of new industry clusters like China.

With containers, it’s hard to imagine China becoming the world’s factory.

Bittersweet

The humble container box has had a dramatic impact on the world.

It led to the diffusion of industry, creating millions of jobs and lifting millions out of poverty.

A dramatic decline in the prices of goods and services across the board due to manufacturing and service offshoring.

Container shipping by decreasing shipping costs enabled capital to go where costs are low. The result is the creation of massive shareholder wealth for shareholders in companies that exploit a globalized world.

Improved infrastructure around port cities in developing and low-income countries. This also leads to other economic spillover effects in terms of employment etc.

But it’s not all been sunshine and roses. Every choice in life is a trade and off, and the same is the case with containerization. While they played a tremendous role in increasing global prosperity and living standards, there have been side effects too.

Labor

Shipping pre-containerization was quite labor-intensive. Hundreds of longshoremen would work on a single ship at a time.

But shipping containers and the automation at port terminals made most longshoremen and other port workers redundant. Millions of longshoremen lost their jobs around the world. Some estimates put this at 90%.

Not just longshoremen, the biggest container ships that carry tens of thousands of containers have crews of 20-30 people.

Port cities, shipping communities, and local businesses

In the breakbulk era, the housing for longshoremen was located around the ports. They were sprawling communities, but containerization decimated a lot of these port cities and communities. Businesses like shops, bars, restaurants, and other businesses catering to dockworkers also had to shut down or move. Several port cities like New York and London, which were once some of the biggest port cities, declined terminally and transformed.

Labor arbitrage

Shipping containers made it possible for manufacturers to find the cheapest places to manufacture their goods. This meant that domestic manufacturing declined, leading to job losses, the decimation of manufacturing towns communities, declining social mobility, and other economic spillovers.

David Autor et al. have vividly illustrated the impact of the China shock on US labor and communities.

Autor, Dorn and Hanson's first peer-reviewed papers from their China Shock saga were published in 2013. The economists found that between 1990 and 2007, trade with China killed about 1.5 million American manufacturing jobs, or about a quarter of all manufacturing jobs lost during that period. But what was even more startling: These losses were heavily concentrated in small- and medium-size communities dotting America's heartland — and workers who lost their jobs in those areas struggled to find other work. The China Shock created what looked like miniature Great Depressions in these places.

While this has led to cheap goods and services, it has led to the mass exploitation of labor in places like China, India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam. Workers are underpaid, get little to no benefits, and toil away for peanuts. Child labor in rare earth raw material supply chains to feed the growing demand for electronics is rampant.

Pollution

The shipping industry is one of the biggest polluters—it’s responsible for about 3% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, or as much as Japan. Containerization led to a dramatic increase in the size of ships. Some of them resemble mini-cities. Ever Ace, one of the largest ships can carry 23,992 TEU (twenty-foot equivalent unit) According to James Corbett, the 200 largest ships produce almost as much sulfur as all the cars in the world.

It’s so bad that shipping emissions are changing the weather on major shipping lanes. Researchers observed twice the number of lightning strikes on shipping lanes compared to other areas.

It’s not just containers

Containers unleashed a revolution, they still needed a few other ingredients. As I was writing this post, I just realized just how important pallets were. Yes, these boring wooden thingies

Similarly, communication technologies enabled the real-time coordination of global supply chains.

Parting thoughts.

The more I dug into this, the deeper the rabbit hole was. In the interest of brevity, I’ll break this post into two pieces and end part one here. I’ve also been following the supply chain crisis that’s still evolving, and I’ll write about it in the next post.

References

The Box – How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger by Marc Levinson This is the definitive book on containerization and I highly recommend reading it.

Sinews of War and Trade: Shipping and Capitalism in the Arabian Peninsula by Laleh Khalili. I came across this book as I was doing some research. I also head a couple of podcasts of Laleh Khalili, the author and she’s fantastic. This book traces the imperial and colonial underpinnings of trade which is another rabbit hold unto itself. I've added this book to my reading list.

A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World by William Bernstein. This was the first time I really dug into how global trade worked and I’ve only gently caressed the surface. I’m a huge Bernstein fan and I’ve heard good things about this book. Hoping to read this soon.

Globalization of American Infrastructure by. Matthew ... Matthew W. Heins

You should check out

There are just too many goddamn things to read and it’s becoming a pain. My colleague Dinesh keeps sharing interesting things at work and he recently started a newsletter to share them. He wastes quite a bit of time so he already does the menial work of filtering nonsense and BS. Check out the newsletter, I know you’ll enjoy it.

How does a container ship work?

If you’re curious about how container shipping works, this is a pretty nice video

So long…