While scrolling through the Substack app, I came across this post by

, thanks to a note from . I loved this part of the intro:We’re talking a bit about commonplace-book-ing today. Not really talking all that much, more simply practicing it, but I’ll give a (very) quick overview either way to start.

In the simplest sense, a commonplace book is a notebook where one collects quotes and ideas and any number of beautiful things from what one has read and learned and seen. Partly for memory’s sake, so you can keep track of what you’ve read, but also as an invitation to deeper reflection. Instead of just letting things go in one ear and out the other, taking the time to record such things gives you the chance to make connections and appreciate what you take in in new ways you might not have otherwise. There are any number of ways to do it, and in truth I do not have a proper commonplace book practice (yet (?)), but I’d like to do something in that vein here.

Partly to share the good work of others, and partly as a reminder to myself that there are plenty of people out there with more interesting things to say than me.

It reminded me why I started this blog: to create a sort of commonplace book. I wanted to share not only my own incoherent thoughts but also the phenomenal work of some amazing people on the internet. I was inspired by a podcast about digital gardening, which is another way of saying it’s a commonplace book, and I loved the metaphor of cultivating something online.

I’m still reading through all the posts that Jessica shared, but I discovered a couple of really good posts.

The first was this beautiful post on motherhood and creativity by Nadya Williams:

It is fine, really. Because this creative activity is not about me, but about something greater—this is about the glorious and surprising strangeness of motherhood in the modern world that does not know how to handle such things. Instead of stifling me, this chaos all around inspires me daily, even if sometimes it can be exasperating. Ultimately, it reminds me that my creativity is not the only one that exists and is not the only one that matters. My children too, the image-bearers of the Creator God who made us all to love art so much as to wish to create something ourselves, are daily creating something. And while not epic by any stretch of the imagination, this life of creativity lived together with them is so beautiful.

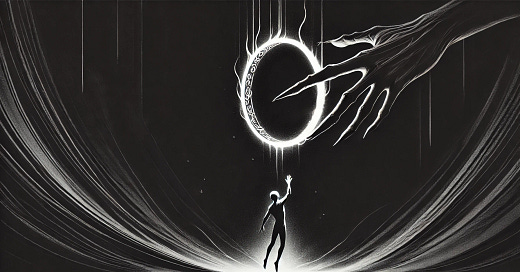

Sauron in our pocket

The second was a thoughtful post on going screen sober by

. The line in bold hit me like a brick because I have a screen problem as well. These damn screens have the same hold on me as the Ring of Power did on Gollum. Even as I write this post, I must have picked up my phone 15–20 times without any real reason.We’ve shelved that experiment (for now—I’m exploring my e-ink phone options, though), so the relevant question has become: how much is too much?

I’m going to let St. Francis de Sales take that one:

“Sports, balls, festivities, display, the drama, in themselves are not necessarily evil things, but rather indifferent, and capable of being used or abused. Nevertheless, there is always danger in these things, and to care for them is much more dangerous. Therefore I should say that although it is lawful to amuse yourself, to dance, dress, hear good plays, and join in society, yet to be attached to such things is contrary to devotion and extremely hurtful and dangerous. The evil lies not in doing the thing, but in caring for it.” (Introduction to the Devout Life)

Don’t hear me saying Francis de Sales would look at how we’re using smartphones and say, “This is fine.” I think it’s worth noting that everything he mentioned in that paragraph would have been done in a group rather than alone.2 That said, “it is lawful to amuse yourself…” but what are the limits? Discerning that means contemplating the difference between “doing the thing” and “caring for it.” And a helpful question to me in that line of thought is: are the stories I’m watching getting in the way of the stories I want to live?

Speaking of screens,

wrote a thoughtful post about Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation. In the book, Haidt argues that smartphones are rewiring teenage brains and leading to an epidemic of mental health issues among them. After publishing the book, Haidt has become the unofficial spokesperson for team smartphones and social media are ruining us all.The book is not without its critics, but regardless of whether smartphones are turning us into fragile beings, I’m happy that we are having the conversation. I haven’t yet read the book, but I’ve followed some of the debates and social media discussions.

Anyway, back to Chris’s post. In it, he correctly points out that it’s not just kids who have a smartphone; adults do too. Unless adults set the right example by using them appropriately, there’s no way the kids will. Here’s an excerpt from the post that I more or less agree with:

I’m squirming because I don’t know what to do with my thoughts after finishing the book. A set of ordered rough conclusions stirs my neurons:

You can’t do much else if you stare at a phone for most of a given day.

Not doing things leads to a series of behavioral atrophies. You lose an edge in the ways of living that you might have practiced without a phone.

Intellectual, conversational, mental, emotional, and social skills slip away.

It’s hard to assimilate into the world when you haven’t practiced and aren’t skilled at doing so.

You might react, poorly, when you don’t fit in. That means isolating, or refusing food, or lashing out at people, or any number of other defensive tactics.

You may start, again, at the top of this funnel, and viciously repeat it until something shakes you out.

Pair Chris’s post with this brilliant perspective by

:We often compare social media to Orwell’s surveillance state of 1984, but here’s what’s different about our telescreens: our screens do not exist to monitor us, but for us to monitor others. There is no totalitarian state behind our screens enforcing social order; instead, the screens turn us into the supervisors of each others’ behaviors.

The danger of social media isn’t that we are being watched, it’s that we become the watchers.

We turn into each other’s audience, judging from afar. We become each other’s data harvesters, knowing who went where, at when and with whom. We even become each other’s digital oppressors: we form a limited perception of who we think someone is based on what they post, and when they do something that doesn’t conform to the imposed image of them, we punish them. “You fell off.” “I was a fan but you went too far.” “Unfollowed.”

This is a brilliant inversion. Pretty much all of the blame for the ills of social media flows outward, but we are equally to blame. What we’ve gotten is as much a result of the choices we’ve made online as it is due to the malevolent machinations of big tech.

Pure random exploration

I love this framing from

, and I agree. As we consume more information online, we seem to have lost our appreciation for the virtues of random exploration. A certain type of sameness is prevalent everywhere as our tastes increasingly reflect the trends of the moment. While that’s good sometimes, we must remain conscious enough not to forget the joy of going off the beaten path.What do you do in a doctor’s waiting room, while standing in line somewhere, or when taking the subway? You scroll on your phone. Some might read a book, others a magazine. Another person might listen to a podcast or music.

The one thing all of these things have in common: they are controlled by algorithms.

Not all of it and not all the time, but chances are, most of the content you consume has been curated for you. While that has its perks and clearly makes consuming content very comfortable, the algorithm doesn’t challenge you to grow. You actively have to decide to grow to make the algorithm change. Random information, however, triggers you to think about something you never would have thought about before. Flipping through the pages of a magazine exposed you to tons of random information you wouldn't have learned otherwise. Similarly, cable TV exposed you to random documentaries on topics you never even considered.

Random information allows you to grow. An algorithm wants to keep you where you are.

Do the weird things

I loved this post by

. Like most people, I went through a phase where I did things for attention, status, approval, etc. But I’ve realized, with time and age, that going down that road is a guaranteed way to be miserable in life. I’ve found joy in doing things that I find fulfilling and enjoyable, even if others find them weird. As Charlie mentions, these odd pursuits have led to some wonderful experiences in my life as well.In an age of social media, resisting the urge to be performative and instead cultivating spaces that allow us to do fulfilling things is important. It’s not easy, but most of the good things in life aren’t. Not every damn thing has to be about likes, shares, and subscribers. There’s a certain kind of joy in exploring without a goal.

I realized that when I think that something is ‘weird,’ it is not really about what I think at all. What I am actually doing is modeling what I think other people will think about it. For example, if I was going to order a lunch delivery, and I thought to myself, “well, I wouldn’t mind a ham sandwich, or a pepperoni pizza, or two dozen raw oysters,” I would probably think to myself, “Oysters? Weird.” But I don’t think oysters are weird, I think that other people will think it’s weird.

Weirdness is a construct that is a stand-in for other people’s expectations.

So if I have a bunch of equally viable options, I should pick the weirdest one, because it means that is the one that is truest to me. It means it has had to elbow its way in past what other people think, other people’s expectations, and any insidious fear I have of being judged for doing what I want or what I think is right. In the scenario above, yes other people might find it strange, but I should Doordash two dozen raw oysters.

And looking back at my life, I can easily find examples where I did something ‘weird’ and it went great, and where I didn’t do what was ‘weird’ and it was terrible.

Pair this with this thoughtful post by

on thinking vs doing:Those with analysis paralysis can’t execute and those with over-confidence shouldn’t execute. Doubt and uncertainty are valuable to have and embrace which keeps us curious and humble. So “Let it rip” with structure in your goals, discipline in execution, and embracing doubt and uncertainty as motivators against overconfidence.

And this comment on the post:

Debilitating loops

As someone who struggles with debilitating spirals of anxious thoughts and rumination, I loved this passage from

’s post:That line has stuck with me for years: leaving a space empty so that God can rush in. If I’m too in my head, there’s no space left for inspiration. If you’ve ever been in an obsessive anxiety spiral, you know exactly what I mean: you get trapped into this loop that just gets tighter and tighter, less and less fulfilling. You’re not going anywhere; you’ve caving in. Being in my body feels like the opposite of that. I feel expansive and relaxed and able to notice the environment around me.

Yes, you can

A brilliant post from

on giving yourself permission to do hard thingsBut sometimes I just want to say—guess I am saying—you know, you don’t need to wait for somebody to tell you it’s okay to plunge into the deep end. You don’t need to wait for somebody’s respect, or to have precisely the right set of books lined up, or anything else. You can just do it. You can just read Hegel if you want. And if you fail, you’ll learn from that failure and then try again better (if you want to). But nobody can stop you, except yourself. They don’t issue licenses at the library, beyond the usual card. And I hope that even operating under a set of drastically reduced expectations, students are still experiencing the pleasure of expecting to sink and realizing that hey—they can swim.

Classics

I’ve never read Dostoevsky, Nabokov, or any of the great Russian masters. In fact, I’ve managed to spend a quarter of my life avoiding the delectable fruits of the great classics. I started to regret it at the beginning of this year, and the regret has only grown stronger as I read this beautiful post by

. I can’t wait to dive into the works of Dostoevsky and Nabokov.Dostoevsky, by contrast, was not so much of a wordsmith, not so much of a man obsessed with language so much as an author obsessed with story, plot, character, human tragedy, deep introspection, the search for love and hate, good and evil, right and wrong. His sensibility was to eavesdrop, to hear and see everything around him and to record it, and to record every single sensation and emotion within himself and, to whatever extent possible, within others. Dostoevsky wanted to genuinely understand The Human Condition, to crack open the sacred fruit that is the human heart, to look inside of a human soul and see what lie at the core.

Irish connection

Did you know Jonathan Swift of the Gulliver’s Travels and A Modest Proposal was a pioneer of microfinance? I didn’t. This post by

is phenomenal and I thoroughly enjoyed reading it:Both through the sales of his books, and his position as Dean, Swift amassed substantial personal wealth – some of which he wanted to use to help the poor. At some point in the 1720s, Swift started a fund with £500 of his own money, and began making interest-free loans sized between £5 and £10 aimed especially at “poor industrious tradesmen”. Swift’s fund had two distinctive features, which made it structurally almost identical to modern microfinance. First, borrowers were expected to make partial repayments on a weekly basis. Second, in order to get a loan from Swift, you had to provide signatures from two people who knew you and attested to your good character. The primary account of these loans comes from a biography written by his godson Thomas Sheridan. Sheridan says that it was a “maxim” for Swift that, due to the co-signing mechanism, “any one known by his neighbours to be an honest, sober, and industrious man, would readily find such security; while the idle and dissolute would by this means be excluded.” The system succeeded: due to the high rates of repayment, Sheridan reports that Swift experienced minimal personal loss of capital. This was the case even though the loans required no collateral. It’s also notable that Swift made use of the court system, prosecuting both borrowers and guarantors if they failed to repay.

The less dismal science

From that guy on TikTok to Queen Elizabeth, there is no shortage of critics of economics. In fact, there’s an entire cottage industry dedicated to dunking on economics and economists. Let’s be honest, much of it is well deserved. But most critics rarely offer any solutions.

, however, is not one of them. In this insightful post, he makes the case for embracing forecasting tournaments to improve economic forecasts:However, forecasting tournaments can teach these qualities (as they generate better forecasts) because they relentlessly reward whatever forecasters do to make themselves more accurate and less overconfident. They provide excellent institutional infrastructure for managing forecasting. They generate information about who is performing well and the incentives to match them, enabling experimentation with new approaches, including building teams with diverse skills.

I found this post in his delightful weekly newsletter, which you should subscribe to right this instant. There’s a rich and weird bounty every week and you always discover something fascinating.

That’s all for this week.

Nice complilation!