I don’t know why; it might be sheer coincidence or algorithmic manipulation, but I keep coming back to the topic of information consumption.

In last week’s post, I wrote about how our reliance on algorithms for our informational needs might be turning us into dull and unremarkable individuals with generic tastes and views. I also wrote a bit of a confessional about how my own information consumption patterns might be buggered.

A few weeks ago, I heard Liv Boeree on the Triggernometry podcast talk about the fucked-up state of the media, and I’ve been letting the conversation simmer in my head. When I was thinking about what to write this week, the conversation popped into my head because it’s a natural extension of what I wrote last week.

Here are a few ideas from the conversation:

Idea 1: A willing sacrifice

Liv uses the fascinating metaphor of Moloch, an ancient demon god whose followers sacrificed humans, including children, for gaining power

She uses Molochian human sacrifice as an analogy to describe how individuals, industries, and society as a whole are locked in negative-sum games. The metaphor of Moloch was made popular by Scott Alexander’s canonical post (archive), which I began reading yesterday but haven’t yet finished.

Konstantin Kisin: What's this "Moloch" concept that you've come up with to describe where our media and new media ecosystem is going wrong?

Liv Boeree: Well, I didn't come up with the "Moloch" concept. It actually comes from originally from an old Bible story about this horrible cult that was so obsessed with winning wars they were willing to sacrifice more and more of the things they cared about, up to and including their children, whom they would sacrifice in a bonfire in this burning effigy of this demon god thing called "Moloch", in the belief that it would then reward them with all the military power they could want. So, this sort of story became kind of synonymous with the idea of sacrificing too much in the name of winning and the force of competition going wrong.

Then, in I think 2014, Scott Alexander of Slate Star Codex, or now Astral Codex Ten, wrote this amazing blog post called "Meditations on Moloch," where he basically connected the dots between all of these mentions of Moloch throughout history and put it into modern game theory terms. Because he noticed that there's this mechanism where the same sort of mechanism is driving a lot of different problems in the world, whether it's tragedy of the commons-type problems where companies will take shortcuts to keep their share of the market, using cheap plastic packaging, for example, because that's the most cost-efficient thing they can do, but then it's creating all these negative externalities for the future, like deforestation and environmental problems.

As well as things like arms races, the fact that we ended up with 60,000 nuclear weapons on Earth, far more than we would ever need to maintain mutually assured destruction, is again because of these game theoretic incentives. If your opponent builds up a stronger arsenal, now you've got to do it, and now they've got to do it, and so on. So it's these screwed up short-term incentives that each individual person is technically rational for following, but if everyone does them, it creates these bad outcomes for the world. That's kind of what this "Moloch" thing is, and that's what it has become synonymous with.

I think Moloch is a brilliant metaphor and frame for looking at the existential issues that plague us. The metaphor is a depiction of a system in which individual actors are pursuing what’s good for them. But if everybody does what’s good for them without coordinating and thinking about the system as a whole, actors will be locked in a race to the bottom that leaves the whole system worse off. In other words, it becomes a we have to because, they are situation.

You can see this everywhere, from social media to arms races and climate change: individual actions lead to escalatory dynamics that end with everything going to shit. The cost of one actor stopping or doing the right thing is so high that everybody continues doing the wrong thing even when they know it’s bad.

The first half of the conversation is about how broken both traditional and new media are. The complaints about how traditional and new media companies are broken are nothing new. We’ve all heard about their sensationalist, clickbaity, and rage-baity tendencies ad nauseam. I even wrote a detailed essay about the sorry state (archive) of media last year.

What was interesting to me was her framing of the state of the media using the metaphor of Moloch. Just like those ancient cults sacrificed their children to Moloch for power, media companies are sacrificing trust and integrity for clicks at the altar of Moloch. For example, if one media company does something stupid but gets clicks, others will follow, and before you realize it, everything goes to shit. We saw this starting around 2013, when BuzzFeed pioneered viral formats like listicles and clickbaity headlines. Soon, even respectable publishers like The Washington Post and The New York Times were forced to follow BuzzFeed.

The drive to do what’s right for oneself has led to a situation where actors are locked in a race to the bottom, unable to coordinate even to ensure their own survival. She calls Moloch the god of negative sum games.

That the media is broken is not breaking news. 'If it bleeds, it leads' has been the business model for many media companies since the invention of the printing press. Here’s an excerpt from my post:

While it’s easy to write about the history of news in a neat sequential order, the evolution of news was anything but. It's messy, chaotic, and unpredictable. To give an example, soon after the invention of the Gutenberg press, one of the earliest things to have been published was erotica:

Among the early books printed on a Gutenberg press was a 16th-century collection of sex positions based on the sonnets of the man considered the first pornographer, Aretino—a book banned by the pope.

Negativity sells because it takes advantage of our deep-rooted human tendency to overweight negative news.

We conducted our analyses using a series of randomized controlled trials (N = 22,743). Our dataset comprises ~105,000 different variations of news stories from Upworthy.com that generated ∼5.7 million clicks across more than 370 million overall impressions. Although positive words were slightly more prevalent than negative words, we found that negative words in news headlines increased consumption rates (and positive words decreased consumption rates). For a headline of average length, each additional negative word increased the click-through rate by 2.3%.

Study after study shows the same thing.

Here's another fascinating study that illustrates the shift in sentiment in news coverage by major US media outlets from 2000 to 2019. I would wager that the result would be similar in much of the developed and developing worlds.

This work describes a chronological (2000–2019) analysis of sentiment and emotion in 23 million headlines from 47 news media outlets popular in the United States. Results show an increase of sentiment negativity in headlines across written news media since the year 2000. Headlines from right-leaning news media have been, on average, consistently more negative than headlines from left-leaning outlets over the entire studied time period. The chronological analysis of headlines emotionality shows a growing proportion of headlines denoting anger, fear, disgust and sadness and a decrease in the prevalence of emotionally neutral headlines across the studied outlets over the 2000–2019 interval.

And wouldn't you know it? There's some evidence for the pervasiveness of a negativity bias around the world.

That said, our results demonstrate a broadly cross-national negativity bias in responsiveness to video news content, while at the time demonstrating a very high degree of individual-level variation. This individual-level variation has important implications for how we understand news production. Most importantly, it suggests that audience-seeking news media need not necessarily be drawn to predominantly negative content. Even as the average tendency may be for viewers to be more attentive to and aroused by negative content, there would appear to be a good number of individuals with rather different or perhaps more mutable preferences.

— Cross-national evidence of a negativity bias in psychophysiological reactions to news

If you look at negativity bias from an evolutionary lens, it makes perfect sense. For 99.9% of human history, we lived in a dangerous world where death was lurking around every corner. In this hostile environment, our brains evolved to keep us alive at all costs.

The cost of not running the moment you heard a rustling in a bush was far higher than running. If you didn’t run, odds are you’d be a happy meal for a lion or cheetah. This explains why our brains are more attuned to negative stimuli than positive stimuli. One study found evidence of negativity bias in infants as young as 7 months old—no wonder babies are annoying.

So, a lot of media companies have learned how to take advantage of the fact that human brains overweight negativity and prefer novelty. It’s the easiest growth hack ever. What’s new is that even principled-ish media companies are no longer able to retain a sane voice. As tragic as it sounds and as painful as it is for me to write, it’s hard to build a sustainable media business while doing all the right things. Selling small parts of your soul is mandatory for survival.

The problem is that selling tiny parts of your soul is a vicious circle. When you are stuck on a tiny patch of land surrounded by an ocean of shit, sooner or later you will take a dip. The end result is a media ecosystem that has gone barking mad, with a lot of barking and madness. The tabloids were the first to figure out the power of negativity and novelty. Today, everything is becoming tabloidified.

It’s the same with social media as well. If you want to get attention and followers, you have to do ridiculous things. But if you start doing stupid things, then other people will escalate, causing a race to the bottom. In one interview, Liv mentioned a remark by Tristan Harris, the co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology (CHT). I looked it up and found this brilliant elucidation from one of his Senate testimonies:

At Google, I worked as a design ethicist, where I contemplated how to ethically wield influence over the thoughts of 2 billion people. In an attention economy, where attention is the limited resource, the advertising business model always seeks more. This results in a race to the bottom of the brainstem. It begins gradually. To capture your attention, I introduce slot machine-like "pull to refresh" rewards that create small addictions. I remove stopping cues for "infinite scroll" so your mind forgets when to divert its focus.

However, that isn't sufficient. As the competition for attention intensifies, we must delve even deeper into the brainstem, affecting your sense of identity and addiction to receiving attention from others. By incorporating metrics such as the number of followers and likes, technology manipulates our need for social validation, leading people to become obsessed with constant feedback. This, in turn, has contributed to a mental health crisis among teenagers.

The next phase of the attention economy revolves around competing on algorithms. Instead of splitting atoms, it divides our nervous system by calculating the perfect content to keep us engaged for longer periods – the ideal YouTube video to autoplay or news feed post to display next. Now, technology analyzes our every action to create avatars or voodoo doll simulations of us. With over a billion hours consumed daily, it seizes control of what we believe while undermining our civility, shared truth, and tranquility.

— Tristan Harris

Moloch has more devotees today than ever before.

News media companies are sacrificing trust and integrity for clicks and becoming entertainment companies.

Individual influencers on YouTube and other social media platforms are sacrificing their integrity and even their well-being for the sake of views and likes.

Countries are sacrificing a brighter future for the sake of a pleasant afternoon.

Idea 2: Circling the drain — Moloch everywhere

Speaking with Liv Boeree, Gus Docker, the host of the Future of Life Institute Podcast, mentioned that once you start thinking about the Moloch metaphor, you begin to see Moloch-like situations everywhere. He's absolutely right. You can see Moloch fucking around with us everywhere.

Take the cases of individualism, utilitarianism, and libertarianism. These ideologies are a big part of western identities. The belief that people should do what’s in their enlightened self-interest has become gospel even in developing countries with collectivist cultures. As tempted as I am to go on an anti-libertarian screed, I’ll resist. But the problem is that rational decisions at an individual level can lead to insanity at a collective level.

Liv Boeree: Whenever people optimize for winning a short-term, narrow goal at the cost of the long-term whole, it can be described in economic terms as a failure to internalize the externalities of the competitive process they are participating in. This is often the case in situations like market failures and pollution.

For instance, consider a scenario where several clothing factories in India are competing against each other with thin profit margins. Each factory owner is incentivized to save costs, and one way to do that is by not investing in expensive filtration systems to prevent pollution in the nearby rivers. Since there may be lax checks and balances in place, each factory owner may quietly pollute the river, knowing that if one factory does it, the others might as well do it too. In this case, they are failing to account for the external costs of their competition, as they reap the profits while externalizing the environmental costs to the wider commons.

This example illustrates how in certain competitive environments, participants focus on short-term gains and neglect the long-term consequences and externalities, ultimately leading to detrimental outcomes.

While not all individual rationality is bad, there are plenty of scenarios where it could lead to coordination failures on a global scale.

Idea 3: Psychosecurity

I had never heard of the term “psychosecurity” or the probable coiner of the term, Patrick Ryan, but I love it. It’s never been harder to distinguish lies from the truth. “Psyhcosecurity” is a fascinating encapsulation of what I think is going to be an important life skill in the years to come—the ability to distinguish truth from bullshit. In June last year, there were a barrage of tweets claiming that an AI-powered drone decided to kill it’s pilot. It was a fake story, and even I fell for it 😢

As Liv rightly alludes to, AI is going to make this worse. I think it’s good to operate under the assumption that AI is going to tear apart our information ecosystem.

Liv Boeree: Patrick Ryan came up with this term "psychosecurity," and he's been saying like the biggest issue of this decade, in his opinion. I'm not sure if I would completely agree, but that we all need to be thinking about and working on is this idea of psychosecurity, same as you'd have cybersecurity for your computer or physical security for your house or whatever.

We need psychosecurity to protect ourselves from the increasingly powerful manipulation tools that are flying about on the internet. And whether these tools are being used because someone is evil or whether these tools are being used because they're simply stuck in a for-profit incentive game that makes you, you know, they're funneling, they're trying to just maximize their profits, so it's like more the game that's evil. It doesn't really matter.

The point is we're spending more and more time on these devices, and these devices have not really been built for all like mental health. They've been built for, again, kind of either maximizing profits or maximizing, you know, just getting people to stay on them for as long as possible. And so how do we build these psychological defenses against these various things? Whether it's like TikTok trying to just turn you into a drooling fucking moron just scrolling a thing or the media trying to turn you into a like rabid person. It's how do we build up these psychological defenses without going full-on and going like, "Okay, no more phone for me." And It might be that's right. And the thing is AI is going to make this more like speed all this up.

We’re already at a stage where people use the term “alternative facts.” The brilliant Ricky Gervais brilliantly framed it in his inimitable style:

There's this new thing of "winning is more important than being right." Right? And it started and it started with social media, it started with political correctness where people now believe that they quite rightly believe their opinion is worth as much as someone else's opinion. But even if your opinion is worth as much similar this opinion, people now think their opinion is worth as much as other people's facts.

It's the world gone crazy that the alternative facts. What? We used to call them lies.

You can see one version of an AI future. In the last 6 months, several reputable media companies, such as CNET, G/O Media, and Sports Illustrated, have faced serious backlash after publishing AI-generated articles with significant factual errors. Life has never been harder for media companies, and barring the giants, all other media companies are battling for survival and cutting staff to the bone.

As this year progresses, I won’t be surprised if the long tail of struggling news publishers fires most of their staff and starts publishing AI-generated news articles. News Corp. is already publishing over 3,000 AI-generated news articles a week. All of this is from reputable media companies and giants of yesteryear. Imagine what the shady actors will do.

I’ve been thinking hard about potential solutions. In last week’s post, I talked about the importance of being deliberate and curating what goes into your brain. However, I think I may have jumped the gun. You need to have the ability to distinguish sense from nonsense. The skill of discernment is like a muscle; it takes a long time to grow and needs constant exercise, or it’ll atrophy.

The only way I can think of building this muscle is to read widely and deeply. Just like artificial intelligence systems are trained with mountains of data, you need to train your brain by consuming a ton of information. You can’t just train your brain with good stuff; you have to ingest a lot of garbage as well. If you do this, your brain will become adept at distinguishing the good from the bad. As I grow older, I’ve started to appreciate the importance of reading classics. A book becomes a classic because it has stood the test of time, so the odds of it being poor are lower. In other words, classics are Lindy.

The Lindy effect (also known as Lindy's Law[1]) is a theorized phenomenon by which the future life expectancy of some non-perishable things, like a technology or an idea, is proportional to their current age. Thus, the Lindy effect proposes the longer a period something has survived to exist or be used in the present, the longer its remaining life expectancy. Longevity implies a resistance to change, obsolescence or competition and greater odds of continued existence into the future.[2] Where the Lindy effect applies, mortality rate decreases with time.

You shouldn’t consider the classics as gospel, but rather as a foundation to build upon.

Read these things

How to improve social media - Part I (archive)

The ideal vision of a public sphere, where public opinion is formed, portrays a marketplace of ideas where the best concepts prevail. A challenge to this vision arises from the fact that people are not typically motivated to seek the truth, engage in thoughtful discourse, or present the most rigorous arguments. Instead, they often strive to persuade others that their standpoint, usually aligned with their self-interest, is correct, and they seek the most persuasive rhetorical strategies to achieve this goal. Consequently, individuals tend to search for conveniently supportive narratives and ideas. Rather than functioning as a marketplace of ideas, our public sphere often resembles a marketplace of rationalisations.

A Hunger for Strangeness: A Cryptids Reading List - Longreads (archive)

It’s a peculiar thing that we both hate and crave the unknown simultaneously. While our rational selves reject that which hasn’t been found or proven, our irrational selves yearn for it. In many cases, an unwavering belief in fantasy was a necessary condition for profound discoveries. However, as modernity encroaches on the irrational, our desire to cling to fantasy grows stronger. Life feels meaningless without a touch of magic.

Take the case of mythical beasts like Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster. While no sensible person would believe in the existence of these creatures, the same was once true for many other previously undiscovered species. But what drives someone to believe in these enigmatic beasts? Here's a collection of some amazing articles on our enduring fascination with mythical creatures."

How Ludovic Phalippou Became the Bête Noire of Private Equity

A good profile of Ludovic Phalippou. The good professor has done more to break the myth that private equity is a magical asset class that delivers equity returns with half the volatility.

As Phalippou puts it in “The Billionaire Factory”: “Why are trustees, investment teams, external managers, consultants not seeing through this? Maybe because their livelihood depends on them not seeing it, especially for consultants. Net-of-fee performance of PE funds being superior to that of public equity is the sine qua non condition for continued employment of at least 100,000 people. The importance of this condition might explain why the mantra of ‘PE outperforms’ has, for many people who work in and around PE, become a quasi-religious article of faith. Merely to question it is considered heresy: Either you believe and you are one of us, or you question the existence of outperformance and you are an enemy.”

I first discovered the professor’s work when I was writing about how institutional investors are just as stupid as retail investors. His work is brilliant and has shaped a lot of my thinking about private markets.

AI holds tantalising promise for the emerging world

Each country will shape the technology in its own way. Chinese chatbots have been trained to keep off the subject of Xi Jinping; India’s developers are focused on lowering language barriers; the Gulf is building an Arabic large language model. Though the global south will not dislodge America’s crown, it could benefit widely from all this expertise.

On Craftsmanship: The Only Surviving Recording of Virginia Woolf’s Voice, 1937 – The Marginalian

Since the only test of truth is length of life, and since words survive the chops and changes of time longer than any other substance, therefore they are the truest. Buildings fall; even the earth perishes. What was yesterday a cornfield is to-day a bungalow. But words, if properly used, seem able to live for ever.

Letters From the Unconformed. “Drowning” in a tsunami of content

This article hit a nerve.

Keith actually composed a response to his own question in his post: Finding Cognitive Liberty -When the internet feels like a full-time job. At the core, he concluded:

First, I must accept my own cognitive finitude. I must concede that there are just some things I can’t or won’t know. The words “I don’t know” should come out of my mouth and off my keyboard more often. There are only so many hours in the day and it is just inescapably the case that I must choose what to attend to and what to ignore. This invariably means being less reactive to provocations that show up in my inbox and on my news feed.

…Second, I must learn to recognize when the thing I am being nudged toward attending to has nothing to do with my actual life, or is something over which I have no actual control or influence.

…And third, I think we should unreservedly lean into “creaturely pursuits”, making them the bellwether which guides our assessment of those clamoring digital diversions.

Steroid to Heaven. The wide world of anabolics

This was a brilliant article on the use and abuse of steroids among people ranging from sportspeople to influencers.

As Adorno noted in his writings on astrology, individuals’ awareness of their dependence on knowledge systems that exceed their grasp is closely associated with authoritarian conformity; for the same reason, young steroid users, faced with the complexities of organic chemistry, are likely to turn away from the hundreds of studies on PubMed and seek out some loudmouth with nineteen-inch arms who tells them what they want to hear. Perhaps this is an occasion for harm reduction, for accepting the reality that some people want these drugs and will take them, and that society’s duty is to keep them safe as they do so.

From Twitter a.k.a. Majestic busstand public toilet wall

Agustin Lebron on the LLM as a put option on cognitive tasks.

Why do such obvious tweets get the most engagement?

I loved this tweet from Brent Beshore

Ramayana as a tweet thread 😲 The next great novel will be a thread! Mark my words; it’s all downhill from here.

😲 That’s some claim. Poor Epicurus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius. They missed out on being the most cited authors on Google Scholar by a few centuries.

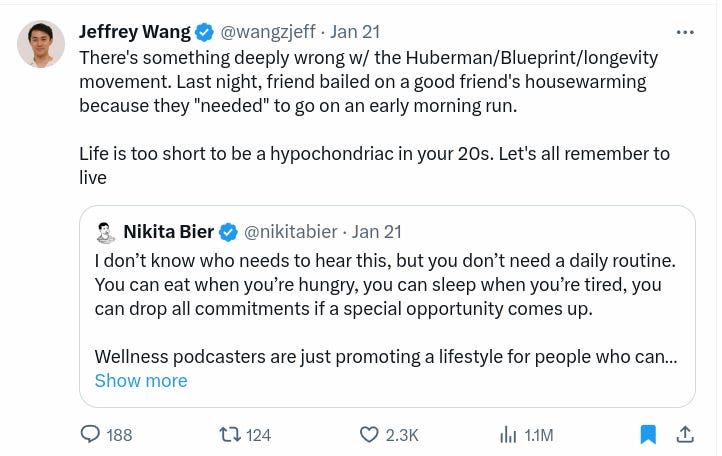

🤣 I mean, if you are not doing ice baths, eating 125 grams of supplements a day, sniffing weird mushrooms that grow near public toilets, drinking your urine, tanning your nut sack, and jogging with a cement block, do you even care about your health? Tweet